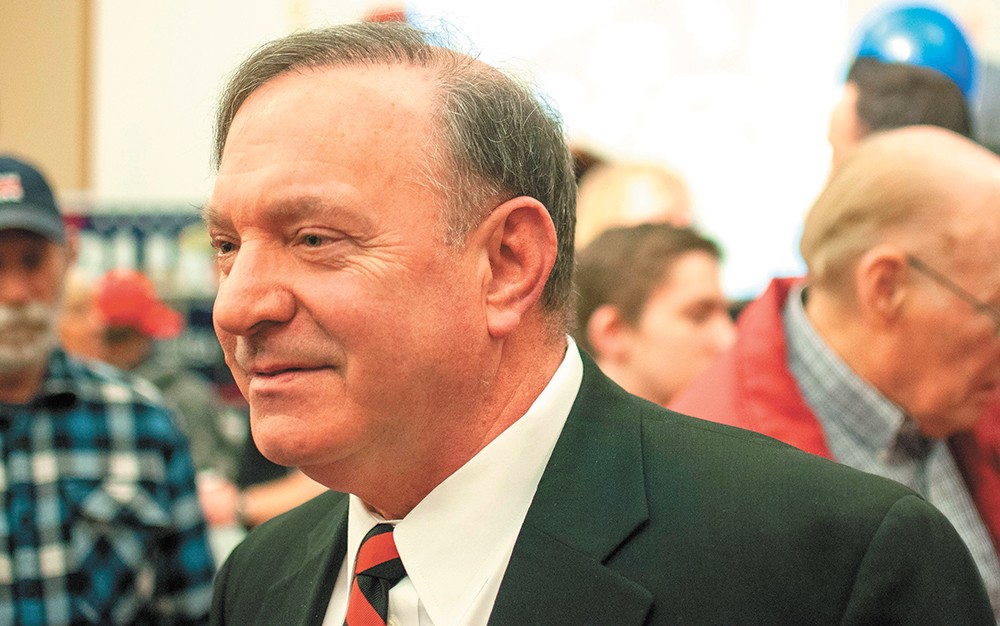

Larry Haskell doesn't negotiate with chronic criminals. As Spokane County's top prosecutor, he prefers a mathematical approach based on the crime, not the person — a practice that critics have characterized as "vending machine justice."

Haskell's refusal to negotiate, judges and defense attorneys say, is resulting in lengthy and expensive prison sentences, as prosecutors often ignore an individual's circumstances (including drug addiction or mental illness) and treat people like numbers on a page.

People like Franklin Scruggs.

Scruggs is a 47-year-old homeless drug addict. Last September, he's standing in front of Judge Maryann Moreno after cops found meth in his pocket.

Citing Scruggs' long record of drug and property crimes, Deputy Prosecutor Patrick Johnson asks the judge to lock him up for the maximum time that state law allows: 24 months. Scruggs' attorney protests. He's a nonviolent drug addict, and he needs treatment, not prison, she tells the judge.

But under one of Haskell's internal rules known as the "9+ policy," prosecutors won't consider treatment options for Scruggs because of the 11 felonies on his record, noting the fact that treatment previously failed to work for him.

Judge Moreno talks with Scruggs from the bench before making her ruling. He tells her about his almost two-decade fight with addiction, his success in previous treatment, his probation in Idaho (from another drug charge) and his nearly 2-year-old daughter.

Moreno tells the man she hears a version of his story all the time. An addicted, mentally ill or otherwise impoverished individual gets trapped in a cycle of "status crimes."

From the bench, she condemns Haskell's policy and gives Scruggs the lowest possible sentence: one year.

"My policy and my procedure

Attorneys, judges and "smart justice" advocates criticize Haskell for pursuing prison time over other options that are proven to more effectively reduce recidivism, and in some cases save money.

Now they are speaking out against Haskell with greater urgency because they believe that he's in line to become the region's top federal prosecutor, working in concert with the Trump administration on what they view as outdated or regressive policies.

"Would Larry be the federal prosecutor who starts going after marijuana crimes on a federal level, here?" Spokane County Public Defender Tom Krzyminski asks. "I think he would."

For his part, Haskell acknowledges that his policy takes away some discretion from deputy prosecutors, but says that those "guidelines" ensure equal treatment under the law.

"It cuts both ways," he says. "It's not only to make sure somebody doesn't go too easy ... but it's also to prevent people from going the other way, and saying 'No deals.' The goal is to treat people similarly."

As for the job with the feds? Haskell, an early supporter of Trump, confirms that he applied, but has yet to hear back.

"I look

Haskell's 9+ policy went into effect in January 2016. It says that for chronic offenders with nine or more felonies, deputy prosecutors won't consider any plea deals; in turn, they will ask for the maximum jail time and cannot offer therapeutic courts, such as drug court or the local mental health court, without approval from Haskell himself or his second in command.

"We're not asleep at the wheel," says Johnson, the deputy prosecutor on Scruggs' case. "We're looking at people who commit the most

But when considering whether someone should qualify for alternative courts — such as drug court, which considers a person's addiction issues — prosecutors weigh previous failed attempts at treatment. "I believe the community is better served by them not committing more crimes ... creating more victims and doing their treatment in [prison]," Haskell says.

Even critics of the 9+ policy, like Moreno, concede that it has an upside: It closes a loophole known as the "free crime doctrine."

Say that a repeat offender gets arrested and is released before trial. In the meantime, he commits a slew of burglaries. He knows that because these sentences are typically served at the same time, his punishment won't get any worse, no matter how many more people he steals from.

Now, the policy holds criminals accountable for each new crime. But it still comes at a cost.

"When you have these overarching policies that say we're going to prosecute you to the max, it doesn't make for smart justice, if you ask me," Moreno tells the Inlander. "It doesn't save the community from this individual who gets out the same way they went in or worse, and then here we are again. We can lock all these people up and spend 150 bucks a day, but I don't think we're getting enough bang for our buck here."

Krzyminski, the public defender, shares a similar view of Haskell's approach. "Their focus is on certain things, which I believe is to lock people up. That's going to be the end result. The weird thing, though, is we have this MacArthur grant, which says we should be trying something new and different and reducing the jail population."

Last year, Spokane County was one of 40

"For me, an unintended consequence [of Haskell's approach] could be that someone charged with a violent offense, but who doesn't have the criminal history, is getting a deal because the prosecutors are spending other resources on these 9-pluses," Krzyminski says. "I think things like that can happen."

When Scruggs' public defender tried to get him into the drug court last year, he was denied by prosecutors because he had too many felonies and had previously failed at treatment. However, defense attorneys say, it's people like Scruggs who should be given priority for drug court.

Research into Spokane's drug court released in December specifically examined the impact of Haskell's policy. The results indicate that the very people restricted from drug court because of the policy are those who stand to benefit most. Those with long criminal records who go through drug court are less likely to

"

Haskell says he's not persuaded by the WSU study.

"I can't emphasize enough that I firmly believe that drug treatment needs to happen early," Haskell says. "It is better for them, they will have

He adds that a supervisor must also approve treatment for offenders with between five and eight felonies.

Sandra Altshuler, Spokane County's drug court coordinator, says that perspective contradicts the vast body of research on drug courts nationwide.

"The research shows that drug courts are most effective for people with addiction that is deep-seated," she says. "There's a tremendous amount of research that shows addiction as an insidious disease that's difficult to treat, and people average nine treatment stays before they're successful. Having them do it early is less effective."

Indeed, the number of people who participated in drug court dropped by more than 44 percent in 2015 under Haskell, compared to the previous year. The program is now operating at less than half capacity.

"In a community this size, with rates of addiction and the issues of behavioral health that we see in the criminal justice population, there's no reason that court shouldn't be full and have a waiting list," says Spokane Regional Criminal Justice Administrator Jacqueline van Wormer.

The alternative court provides much more intense supervision than traditional probation and measures success differently, Altshuler says.

"We sanction [offenders] for lying and deception, but not for someone coming forward and saying, 'I relapsed last weekend,'" she says. "That just means they need more treatment, and that's why we're here. The overall goal for drug court is for them to change their entire life."

Scruggs tells the Inlander he wanted to participate in drug court, had prosecutors given him the chance. After nearly a year behind bars, he was released from prison in October 2016 and is serving probation. He takes drug tests and goes to outpatient treatment twice a week. But he's been through this before. In 2013, he says, he completed inpatient drug treatment, but it didn't stick.

He's optimistic that the treatment will work this time. It has to, he says, so he can have a relationship with his young daughter.

"As the first year is always the hardest, I do have my work cut out for me," he writes in a personal note to the judge. "I will not be that deadbeat dad like so many before me. I want my daughter to say and be proud of the fact that I'm her dad."

Haskell's 9+ policy is not the only area where his philosophy is drawing the ire of judges,

• Juvenile Justice: In November 2015, the Inlander published a report detailing changes to how prosecutors approach juvenile crime under Haskell:

The number of charges filed against kids increased. "Alternative case resolutions" — where attorneys construct solutions without a conviction — were no longer an option. And in some cases, prosecutors insisted on bringing charges despite victims' wishes. Together, these changes indicated a "get tough" mentality, defense attorneys

Back then, Haskell denied that his office was moving away from a rehabilitative bent for juvenile offenders. "We're here to protect community safety and due process," he said. "Accountability is very important, but rehabilitation is not a statutory requirement."

Technically, Haskell was right. The word "rehabilitation" was not a part of the Juvenile Justice Act until state lawmakers added it in 2016. The change brings Washington state in line with research and case law on juvenile crime.

"These sort of get-tough policies for adolescents are contrary to everything we know

Since the change to state law, public defenders in Spokane say that not much has changed.

"Once Larry took over, he basically started treating juveniles as adults," says Krzyminski, the public defender. "There's no difference in the prosecution of a juvenile than an adult."

Juvenile Public Defender Krista Elliott says that prosecutors still don't consider rehabilitation when weighing criminal charges. "There are so many things that Haskell is not doing even when prosecutorial organizations and his peers are following these guidelines," she says.

Haskell defends his office's strategy, saying state law requires that rehabilitation

"You know the old pipeline to prison?" Haskell says. "We're trying to change that perception where it's really a pipeline to services, and the reason is, if we don't charge them, they can't qualify."

• Driving Under the Influence: Last July, Haskell announced a hard line on drinking and driving.

"A DUI is an unguided missile that is one interchange away from a direct hit," he told reporters during a press conference explaining the new policy.

For repeat DUI offenders, prosecutors are no longer offering a reduction to a lesser charge, and to some that

"'Unguided missiles' is just a slogan like 'Make America Great Again,'" says Spokane attorney David Miller. "It means nothing."

Miller says a prosecutor's job is to evaluate each case based on individual circumstances, not by a policy.

Deputy Prosecutor Rachel Sterett, who supervises attorneys handling DUI cases, says the office came up with the new policy after comparing practices in Spokane to other counties throughout the state. She says Spokane had been more lenient than some neighboring counties.

The United States locks up more people — as many as 2.3 million by some counts — than any nation on Earth, with most individuals behind bars in state prisons and local jails. Mass incarceration in America skyrocketed in the 1980s and '90s. The cause of such an explosion, traditional thinking says, can be attributed to the War on Drugs and harsh sentences for drug and repeat offenders. While those policies certainly deserve some of the blame, that's not the whole story.

Fordham University law professor and economist John Pfaff points to the daily decisions of local prosecutors, such as Haskell. In his new book Locked In: The True Cases of Mass Incarceration and How to Achieve Real Reform, Pfaff suggests that the spike in prison populations, particularly in state prisons, which hold the majority of offenders, is largely due to an increase in felony charges filed in the 1990s and 2000s, despite decreasing violent and property crime rates overall.

"In the end, the probability that a prosecutor would file felony charges against an arrestee basically doubled, and that change pushed prison populations up even as crime dropped," Pfaff writes.

In the two years that Haskell has been Spokane County's top law enforcement officer, criminal filings have increased by about 6 percent for adults and 15 percent

To his credit, Haskell has jumped on board with many reforms called for in A Blueprint for Reform, a 2013 report with suggestions to improve the criminal justice system in Spokane County. For instance, rather than charging all people criminally for driving on a suspended license, prosecutors usually give them an opportunity to reinstate their license in lieu of charges.

He's also signed onto all of the reforms being supported by the MacArthur

In the end, Haskell says he's open to second chances for first-timers, but for repeat offenders, he balances different interests — justice, public safety, the "reasonable" execution of the law.

"

It's a law-and-order philosophy that he would exercise as a federal prosecutor, pursuing hard-line approaches to marijuana,

On Monday, as Trump issued a revised travel ban barring refugees and other travelers from predominantly Muslim nations, Haskell was encouraged by the direction in which America is heading:

"I think we got a federal law on the books about deportation, and I think it should be followed unless it's changed." ♦

About the Author

Mitch Ryals covers criminal justice for the Inlander. He has previously written about confidential informants, bounty