If you haven't been down to Huntington Park, you're missing a gem. From the plaza adjacent to Post Street and City Hall, and on down the winding walk to the lower falls, Avista has perfected a quintessentially Spokane landscape. The view of the monolithic Monroe Street Bridge... the gondolas swaying... the old Washington Water Power building, one of Kirtland Cutter's finest... the roar of the Spokane River falls, especially this time of year... It's an amazing experience, made all the more remarkable because it wasn't long ago that we almost paved right over it.

Never completely forgotten, but never quite the center of attention either, the Spokane falls and river gorge were under threat during the '90s, when the city wanted to build the Lincoln Street Bridge right over the site of today's Huntington Park. Had the bridge been built, there would be no Huntington Park; the wide concrete span would have preempted the singularly magnificent views that have been made so accessible by Avista.

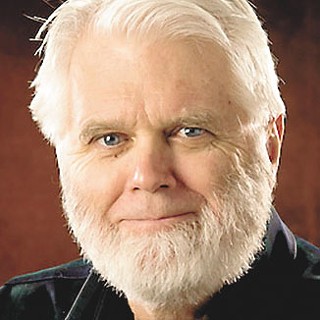

Now the city wants to name the beautiful plaza at the crest of Huntington Park for a citizen who has made an important civic contribution. I second the nomination that has been formally made by the Friends of the Falls: Dr. John Moyer. His medical career alone was noteworthy: Go back a few years, and you'd be hard pressed to find any family in town who hadn't had at least one baby delivered by "Dr. John."

What people don't know is that even after retirement, Moyer — who is getting up there in years but still with us — continued his run out to small-town Eastern Washington. He was our very own Marcus Welby — much beloved and always on call.

Then, of course, there was his political career. A Republican, Moyer won in a Democratic district, the 3rd, and would serve in both the Washington state House and Senate.

But it was Moyer's contribution to the Lincoln Street Bridge fight that begs to be recognized. I had something to do with flagging the issue in a series of commentaries that ran in the Inlander and on KPBX, questioning this project that appeared to be a "done deal." A young local architect, Rick Hastings, agreed with my assessment and did something about it: He organized the Friends of the Falls to defend this priceless feature of our city.

It was Moyer who lent his prestige to the cause when he joined the citizens group a short time later. He also made the case to expand the issue: It wasn't just the falls that were at risk, but the gorge below, too.

At the edge of the falls, under a Spokane summer sky, it's hard to believe now, but the City of Spokane was bent on building a bridge over all of it. It rested its justification on two supposed needs: Fighting air pollution and easing traffic congestion. So the Friends took a closer look. John Covert, a geologist by training and Spokane resident, did his own research and destroyed the city's pollution claims: Their data was outdated, their analysis flawed, their conclusions unwarranted.

At the same time, nationally recognized traffic engineer Walter Kulash came to Spokane for an EWU symposium, and he did to the city's congestion argument what Covert had done to the air pollution argument: He destroyed it. Local developer and preservationist Ron Wells has said that "Walter Kulash changed the debate." (There was another good reason to oppose the bridge; it was to be part of a new Monroe-Lincoln couplet, creating a freeway through downtown. Everybody knows that couplets crush walkability and destroy neighborhoods.)

Still, the Friends of the Falls needed legal help. To the rescue came local attorneys Laurel and Doug Siddoway, who took the case pro bono.

In the end, despite a dug-in, pro-bridge City of Spokane, the Friends of the Falls prevailed and the Lincoln Street Bridge project was defeated.

It remains hard to believe we got that close to catastrophe. In the early 20th century, the Olmsted Brothers identified the Spokane River falls and gorge as the city's defining feature. Before landing on the idea of a World's Fair, King Cole wanted to create a Spokane River Gorge National Monument. Now we have Kendall Yards thriving off its proximity to the Spokane River, Avista's investment at Huntington Park and plans for upgrading Riverfront Park — all made possible by the good citizens who defended the Spokane River.

Dr. John Moyer was one of the most important of those voices: He was someone people listened to, and he spoke out about the bridge precisely when we needed to hear it. So today, due to this profound civic effort, we don't have that bridge over the falls, or that downtown-killing couplet. We do have the start of the kind of Great Gorge Park that the Olmsteds and so many others have envisioned.

The John Moyer Plaza. Overlooking a cherished place he helped to save, that would be a fitting tribute to an indispensable citizen. ♦