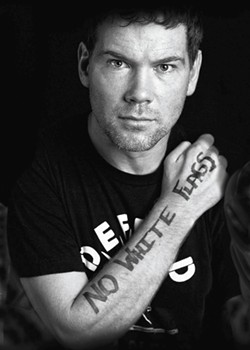

Steve Gleason was a big deal here in the Inland Northwest back when he was blowing up quarterbacks and smacking home runs for Gonzaga Prep. His stature grew when he went on to Washington State and became an improbable star linebacker. In the NFL, he built himself into an even more improbable star.

But that's not why he's going to be remembered. Oh, we won't forget when he led the Pac-10 in tackles. And the story of that blocked punt will be told for years and years to come in New Orleans, and by anyone else who watched that unforgettable Monday night game. In all likelihood, however, he'll be remembered as the guy who fought back against a disease that was thought to be incurable. It's been five years since Gleason was diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS, or Lou Gehrig's disease), a goddamn awful disease that steals your body and leaves your mind there to watch it happen.

This week, we'll hear a lot about Steve Gleason. He's the subject of a documentary hitting big screens in Spokane and across the nation this week, and the music festival that bears his name and benefits his charity will take over Riverfront Park in the days that follow. You'll want to know Steve Gleason.

This is not about a man. This is about a movement...

People still talk about Steve Gleason's high school days at Spokane's Gonzaga Preparatory School. The guy had a knack for making an impression. His stats were impressive, but if you ask someone about what he was like on the field, you're treated with some sort of remarkable and often hard-to-believe anecdote. A bone-crushing tackle or an insane catch in center field.

Dennis Patchin, the local ESPN 700 radio personality, began covering Gleason when he was a sophomore at Prep. He maintains to this day that Gleason was a better baseball player than football player, and that assertion is at least in part due to something he witnessed at Rogers High School more than 20 years ago. Patchin was shooting video atop the press box for that evening's KXLY newscast when Gleason came to the plate.

"He turned on a ball, and as it was flying out of the park it was taking all the air with it. It went over the alley, over a building and hit a guy's house. There was the crack of the bat, and then a cheer and then it got really quiet, and then people knew they'd seen something. It was amazing," recalls Patchin.

But in the halls of the high school, Gleason wasn't a tough guy. He wasn't too cool for you.

"He was always just the ultimate role model. He was the guy in the hall who would say 'What's up' to you and you'd be like, 'Whoa, Steve Gleason just said hi,'" recalls John Blakesley, who was two years behind Gleason at Prep and would reunite with him in 2012 when he helped found Gleason Fest.

When Gleason was inducted into the high school's Hall of Fame in 2011, shortly after being diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, his father read a letter Gleason wrote about his time there. He admitted that despite all the accolades, he wasn't perfect.

"Once, as our basketball team's mascot, I got ejected and watched the second half of our district finals from the top row of the Spokane Coliseum. Who knew you could be ejected for stealing the other mascot's head and tossing it to your student body!" wrote Gleason.

TOO SMALL, TOO SLOW

When Gleason arrived at Washington State University in 1995, he was an underdog. A lot of schools hadn't recruited him. They said he was too small to play linebacker, where he excelled in high school, and probably too slow to convert to play safety, even though the latter wasn't true.

He'd always been the big guy on his youth teams, but he topped out at the 5-foot-11 he reached in eighth grade. He carried 215 or so pounds on that frame at WSU, giving up at least 50 pounds to the offensive linemen he'd often be tasked with taking on. But by his sophomore year, he led the team in tackles. When he was a senior, he led the entire conference.

"There are some intangibles that make up for a lack of size. He definitely has those. Basically, he's a winner," his coach, Bill Doba, told the Seattle Times in 1999.

Gleason was a fan favorite for those four years on the Palouse. He flew across the field, sprinting to the opposite sideline to make a tackle on a play that a lot of guys in his position wouldn't have bothered wasting their time on.

"He played football sideline to sideline," says Patchin. "You knew that you were watching a very good athlete."

When his college career ended, he wasn't selected in the NFL draft. Again the underdog, he found his way into Indianapolis Colts training camp. He didn't make the team, but the New Orleans Saints signed him to their practice squad. Eventually, he made his way onto the Saints roster and played in three games that first season. He'd found a team that believed in him, and a city he'd come to embrace as much as it embraced him.

THE BLOCK

It was one of those games that a lot of people will say they watched live, even if they didn't. It was Sept. 25, 2006, and the New Orleans Saints were playing their first game in the Superdome since Hurricane Katrina — the same Superdome that served as an emergency shelter for the thousands of residents left homeless by the storm and subsequent flooding.

"Deep down, I think everyone on the team wants to bring some joy to New Orleans. The way we can do that is by winning football games. Now it's more than a job," Gleason told the Inlander in 2005 when he and the rest of the team were living in hotel rooms in San Antonio, where the team played three of their "home" games that season.

The atmosphere in the Superdome that September night in 2006 was already electric as a city struggling to get back on its feet finally had something to rally behind, even if it was something so seemingly trivial as a football team. The Saints defense stuffed the Falcons on the first series of the game. Fans still hadn't sat down since the kickoff and the cavernous dome was booming after Gleason's friend, linebacker Scott Fujita, sacked the Falcons' Michael Vick.

The visiting team came out to punt. No one could see Gleason crouched low in the middle of the line. Certainly not the long snapper, who fell for a stunt, leaving Gleason — wearing No. 37, long hair streaming out of his helmet — free to fly directly at the punter. He suffocated the punt and it bounced toward the end zone, where the Saints' Curtis Deloatch dove on it for a touchdown.

Just a minute and a half into their return to the stadium they thought they might lose just a year prior, the city of New Orleans had a reason to celebrate. And they celebrated it for that entire season. The Saints won 10 games. They made the playoffs, where they won just the second postseason game in franchise history. Three years later, the Saints won the Super Bowl.

If Steve Gleason never had been diagnosed with ALS, never became the inspirational figure he's become in his post-football life, he'd still be immortalized in New Orleans history: In front of the Superdome, there's a 9-foot-tall statue of Gleason blocking that punt.

Part of the inscription reads: That blocked punt symbolized the "rebirth" of the city of New Orleans.

"That statue is not about football," Gleason told ESPN upon the statue's unveiling in 2012. "It's a symbol of the commitment and perseverance that this community took on before that game."

WHEN YOUR FAVORITE BAND BECOMES YOUR BIGGEST FAN

J.D. Ward is chatting online with Gleason last week when he picks up the phone at his home in the Southern California coastal town of Hermosa Beach. He's trying to score tickets to a Temple of the Dog show. This is a big deal for both Ward and Gleason. Temple of the Dog was a Pearl Jam/Soundgarden collaboration that has never gone on tour, and both Ward and Gleason have been hard-core Pearl Jam fans since their high school days.

"We used to sit in beanbags in Steve's basement and listen to Pearl Jam. Now, Pearl Jam is part of his group of friends. There's no other way to describe it other than mind-boggling," says Ward, who was a groomsman for Gleason when he married his wife Michel in 2008 and travels to New Orleans about five times a year to see his friend.

Gleason went backstage at a Pearl Jam show after his diagnosis and met guitarist Mike McCready. The two became friends, and soon the band brought Gleason into their orbit. When they needed celebrities to interview them for a documentary to promote their 2013 record Lightning Bolt, they brought in Gleason, who spoke through the computerized voice system that he controls with his eyes.

"The music you guys have created ... has plastered the wall of my adolescent and adult life. It's really been a soundtrack to my entire life," Gleason said. Then he dug in.

"OK, so with my first question. I'm channeling the PJ superfan. It's been five years since Backspacer. That's the longest stretch between records. What the f---?" he asked.

All five members of the band laughed for the better part of a minute. Later, he interviewed Eddie Vedder one-on-one. Gleason brought the frontman to tears, telling him that he was making a video diary for his son Rivers in case the "experts are right" and Gleason passes away while his child is still young. He related this to Vedder's own experience of growing up without a father.

"He's genuinely intelligent," says Ward. "They're not a typical band and he's not a typical guy. He's on the cerebral side, and they connect with that."

When Pearl Jam finally came to Spokane in November 2013 after more than 20 years without playing a show in the city, Gleason wasn't just in attendance — he was part of the show. The band let him put together the set list, and it made for a night of deep album cuts, peppered with hits and rare covers. It was the sort of thing a Pearl Jam junkie can only dream about.

At the end of the show, McCready made his way into the stands, found Gleason and his family and played the last chords of "Yellow Ledbetter" standing next to Gleason's wheelchair.

THE MOVEMENT

Gleason was diagnosed with ALS in January of 2011.

At first, he said he experienced a "mixture of disbelief, frustration and desperation." But it didn't take long for him to enter the next, and perhaps most important, phase of his life.

"I felt that I had a platform that could help change the trajectory of the disease on a global scale," he told the Inlander in 2012.

Soon, he and his wife, Michel, formed Team Gleason, a nonprofit organization seeking a cure for the disease. It also has made a significant impact in finding ways to empower those suffering from ALS, including pushing for technological innovation to make communication, among other things, easier.

"For Steve to have the forethought to help people communicate was amazing. At the start of that journey it was more of an idea, but now the plan has been enacted," says Ward. "You give these people purpose, they'll live vibrant lives."

Gleason uses the technology to type with his eye movements, allowing him to write essays that have been published in various publications, compose speeches and write some of the funnier tweets on the internet. He still has a voice, even if it comes through a computer, allowing him to chat with his wife and 4-year-old son.

In New Orleans, Gleason's stature is tough to explain. A newspaper columnist called him the "moral epicenter of this city." Ward says he's the pope of New Orleans. People look to him for insight, and not because he is a former professional football player. His standing in Spokane is somewhere up there, too.

"Around here, the thing is that Steve Gleason was a football player, and that was his opening line on anything — former Cougar, former NFL player Steve Gleason," says Patchin, the local sportscaster. "That's not the case anymore. It's Steve Gleason, the main proponent for ALS in this country."

Gleason, though, is still fighting this disease, and is past the average length of time that ALS patients live after diagnosis. It's a reality that his family and friends like Ward have to realize.

"It's something that I wake up with every day. Is today that last day that I'm going to talk to my friend? It's crazy," says Ward.

But if you ask Gleason, he doesn't seem to worry about that too much. After all, he's not just "hanging in there," because, as he wrote in Sports Illustrated last week, such sentiments are for posters with kitty cats on them. There's a lot of living to be done.

"In life it's easy to get overwhelmed by distractions and problems. Oftentimes, we get caught in our past or future, rather than experiencing the beauty of the present moment," Gleason told thr Inlander in 2012. "None of us know when we may die, so I think it's important to pursue the activities you love and spend time with people that you love." ♦