Monday, January 9, 2017

What the Coeur d'Alene Press doesn't understand about naming sexual assault victims

When North Idaho College settled a lawsuit this fall with the victim of an alleged

The statement, unexpectedly, named the woman who claimed to be gang-raped.

And so, too, did an article posted that morning, Dec. 1, 2016, by the Coeur d'Alene Press, titled "NIC Settles Lawsuit With Former Student Who Claimed She Was Raped." (If you're curious how North Idaho College mishandled the case, read our story in this week's paper.)

Typically, journalists do not name victims of sexual assault without the victim's permission so as not to shame victims publicly, as the Poynter Institute for Media Studies points out. And the CDA Press, facing backlash, removed the name from the Dec. 1 article by the end of the day.

But why the paper identified her in the first place is revealing.

According to an

But the No. 1 reason? The paper didn't believe she was

And that, experts agree, represents a fundamental misunderstanding of how the media should cover sexual assault.

Most instances of sexual assault are never reported to police in the first place, says Laura Palumbo, communications director for the National Sexual Violence Resource Center. Physical evidence is often limited when it is reported, as was the case with R.R., who went to police months after she says she was gang-raped. And if a news organization deviates from the practice of not naming the victim, like the CDA Press did, that "may suggest to readers the account is not credible," Palumbo says.

"It would be very troubling for an editor to base this decision on assumptions about a victim's credibility," she says.

The Inlander has obtained parts of an email thread between Hurst and the Press. Responding to Hurst, Patrick, the managing editor, explains why the CDA Press made an exception to their usual standard of not naming victims of alleged sexual assault:

"1. The allegations were thoroughly investigated by law enforcement and no charges of any kind were brought. We have read the police reports and done much more background work, and we are convinced [R.R.] is a victim of being manipulated by people with politically motivated interests — not gang rape."

Patrick did not respond to an email, phone call, or voicemail from the Inlander seeking comment for this article.

Elana Newman, research director for Dart Center, a network of journalists that aims to improve media coverage of trauma, says using the fact that charges were never filed against the men R.R. accused should not be justification for naming a victim of alleged sexual violence.

"That's just stupid," she says.

By naming someone without their consent, you are furthering their experience of feeling helpless

tweet this

Maybe the CDA Press has more information than we do. But based on our interviews with law enforcement involved in the case, R.R.'s credibility was not at all the reason it didn't move forward. The Coeur d'Alene police detective on the case, Jared Reneau, described her as "truthful and honest," and said he found no inconsistencies in her story.

And this is what Kootenai County Prosecutor Barry McHugh said when the Inlander asked if the decision not to file charges meant that prosecutors do not believe this incident happened in the way it was reported, or that they do not believe it was rape:

"No and no. We take these allegations very seriously and it would be wrong to characterize the decision to not prosecute in the ways you described," he said. "The decision to decline reflects our evaluation of the evidence in considering our obligation to prove crimes beyond a reasonable doubt."

But that, evidently, is not how the CDA Press interpreted the decision.

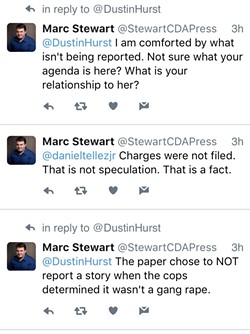

Within hours of Patrick's email to Hurst explaining the reasoning for naming R.R., Marc Stewart, director of sponsored content for the CDA Press, reinforced the paper's decision to name the victim in a Twitter battle with Hurst. "No charges were ever filed. Why is that? #lotmoretothestory," he wrote. "The police determined there wasn't evidence of a gang rape. You keep calling her a victim — but no charges were filed."

Stewart, reached by phone Friday, chose not to comment for this article.

Going by his comments on social media, the decision by prosecutors also influenced the paper to not cover the case when R.R. first went to the paper hoping for them to report it. "The paper chose to NOT report a story when the cops determined it wasn't a gang rape," said another tweet.

He later deleted those tweets, but R.R. had already seen them. She took screenshots that she has provided to the Inlander.

Andrew Seaman, ethics committee chair for the Society of Professional Journalists, would disagree with Stewart's suggestion that the failure to file charges means police determined she wasn't raped.

"The absence of charges doesn't mean the person still isn't a victim," Seaman says.

A more compelling reason to name her, perhaps, would be that she had already named herself on a blog. R.R. tells the Inlander that she wrote the blog because she wanted to share her story with her friends on Facebook. She says she left the post up in case other students with a similar experience wanted to reach out.

"I didn't want to be identified in the media because I didn't want to be criticized or 'known' for that," she tells the Inlander.

But did that blog mean she should lose her right to privacy? That is up to each paper, Seaman says, but he adds that journalists should "err on the side of caution" even if the name is reported elsewhere. And ultimately, it may come down to the news value added by naming the alleged victim. Seaman says naming her in the brief article about her settlement may not reach that threshold.

"In this situation, I feel like reporting a settlement had been reached without identifying details of the victim would suffice," Seaman says.

Since the CDA Press didn't respond to our questions, it's unclear why they eventually removed her name from their article.

Newman, with Dart Center, says the best practice would have been to call the victim and ask her first, something the CDA Press didn't do in this situation. From a psychological perspective, Newman says naming the victim of sexual assault can cause further damage.

"The act of sexual assault or attempted assault is the act of taking away choice from someone. It's about power and control," Newman says. "By naming someone without their consent, you are furthering their experience of feeling helpless."

Tags: sexual assault , coeur d'alene press , journalism ethics , News , Image