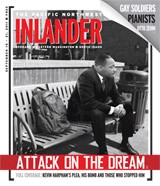

From his seat facing the courtroom door, Kevin Harpham looked directly at the attorneys, the press and the public, all of whom had come to see him plead.

He turned his back to the audience when it came time to speak last Wednesday. Standing at the podium in a white prison outfit, using answers that rarely amounted to more than “yes” or “no,” he told U.S. District Judge Justin Quackenbush about his life and the crime that came to define it.

Yes, it was he who put the backpack full of explosives and poison on the northeast corner of Main and Washington in Spokane on Jan. 17. Yes, he put it there because it was on the route of the Martin Luther King Jr. Day march. Yes, he targeted that march because many of the participants were black, or Jewish, or otherwise didn’t fit into his white supremacist worldview.

When he was arrested last March, Harpham faced a trial on four counts related to the attempted bombing, which could have put the 37-year-old in prison for life. Now, as part of the plea bargain, he could face 27 to 32 years in prison, with the possibility of trimming two months off for each year of good behavior — meaning he could be a free man by the time he’s 60.

If Quackenbush signs off on the agreement, the charge of using an explosive to commit a hate crime, which carries a mandatory 30-year sentence, would be dropped.

“I think what happened speaks for itself,” says Federal Defender Roger Peven, Harpham’s attorney. “Clearly the plea agreement benefited Mr. Harpham.”

U.S. Attorney Michael Ormsby took a different view. “We had a lot of evidence, but trials are a risky thing. You never know what’s going to happen. We think this is a fair sentencing [range] that will allow the community to come to closure.”

Jack Levin, a professor of criminology and sociology at Northeastern University in Boston who specializes in murder and hate crimes, says the case against Harpham was strong.

“In a sense, the defendant was lucky to have admitted planting the bomb, and [he] has a chance of gaining his freedom after almost three decades,” Levin says, adding that older people are generally less likely to commit violent acts.

And there’s the fact that this bomb didn’t go off.

“Had it exploded, I’m certain the government would not have plea-bargained the case,” says Oklahoma-based attorney Stephen Jones. He should know: His client, Timothy McVeigh, was convicted and later executed for his role in the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing.

Federal trials can be tricky. Jones says a federal jury — like the one that would have awaited Harpham — acquitted McVeigh’s accomplice, Terry Nichols, of some of the charges related to the bombing that killed 168 people.

“Even in cases where the evidence appears overwhelming, there can be surprise verdicts,” Jones says. Besides, to avoid the risk of an adverse verdict, prosecutors often choose to plea-bargain to compel a suspect to reveal any of their accomplices in a crime, Jones adds. Ormsby says no other suspects have turned up.

Prosecutors would also have to account for the two-hour gap between when FBI agents arrested Harpham and when he was read his Miranda rights — during which time he made two statements to investigators. Prosecutors had initially tried to admit those statements in court but eventually withdrew their motion.

Peven says he expects to know about 10 days before the scheduled Nov. 30 sentencing hearing whether Quackenbush accepted the plea agreement. If the judge sentences Harpham to a term outside of the plea agreement, then the bargain will be void, and the case could still go to trial.

Bringing closure will take more than a plea agreement, says Ivan Bush, organizer of the MLK march.

“We have quite a bit of healing to do,” Bush says. “This whole bombing thing was more like a symbol or a symptom of some greater need.”

That need, Bush says, is for a dialogue about hate among community members. But in a region with a history of racist violence, others question whether the proposed sentence is enough for a man who plotted to spray shrapnel into people publicly honoring the country’s most revered civil-rights leader.

“It’s not closure. I don’t care what anybody said, it’s not closure,” says V. Anne Smith, president of the NAACP’s Spokane branch. “Spokane has a race problem, and they would like to say they don’t. I would have liked to have seen it go to a jury trial. What the outcome would be no one knows.”

Had Harpham been acquitted, Smith says, “people of color, whoever they are, not just African-Americans, [would] need to get up and leave Spokane.”

Mark Potok, director of the Intelligence Project for the Southern Poverty Law Center, followed the case and says “Harpham is typical of many domestic terrorists of today, in that he essentially operated alone.”

Potok noted that the bombing attempt happened at about the same time as U.S. House Rep. Pete King’s announcement that he would convene congressional hearings into the radicalization of American Muslims. Those hearings did not focus on other domestic terrorists, like white supremacists.

Still, Harpham’s incarceration will likely remind white supremacists of the federal government’s willingness to arrest and prosecute them, Potok says.

“On the other hand, we’re looking at a very conflictive moment in our nation’s history,” he says. “I expect to hear more rancid rhetoric in the coming months as the election season goes on.”

Without a trial, the ideology that drove Harpham to plant a bomb won’t be given a public airing. To Michael Goldsten, rabbi of Temple Beth Shalom in Spokane, that’s a good thing.

“There are plenty of impressionable people who may not on their own go look for it,” Goldstein says. “If it’s out there in front of them, even if it’s a reference in general media, that might be enough to spur their interest in looking further.”

Despite the violence that nearly destroyed the march he champions, Bush say he is hopeful for Spokane’s future. He points to the construction of Martin Luther King Jr. Way, which extends Riverside Avenue east of Division Street in Spokane.

“In my mind, and in my heart, that was not an ordinary street unveiling. That street naming was the unveiling of a statement,” Bush says. “You know, that statement was that Spokane will never be the same again. Spokane is saying we are the community, affirming everybody’s sense of togetherness.”

Comments? Send them [email protected].