The SIERR building could have easily been demolished. And without the right developer, it probably would have been. The land is prime. It sits at the busy intersection of Hamilton Street and Spokane Falls Boulevard. It’s close to Gonzaga and the Riverpoint Campus. There’s freeway access and river views.

And the 105-year-old warehouse had outlived its original use of repairing Spokane’s electric trains at the turn of the century. The building has an austere industrial beauty, but it’s not lavish, certainly not the sort of place big-money donors or city governments fall over themselves to preserve.

When McKinstry CEO Dean Allen was scouting locations for the company’s Spokane office, though, he caught a glimpse of the building while sitting at a traffic light. Kim Pearman-Gillman, McKinstry’s business development director, says Allen told the realtor, “I want to see that one.”

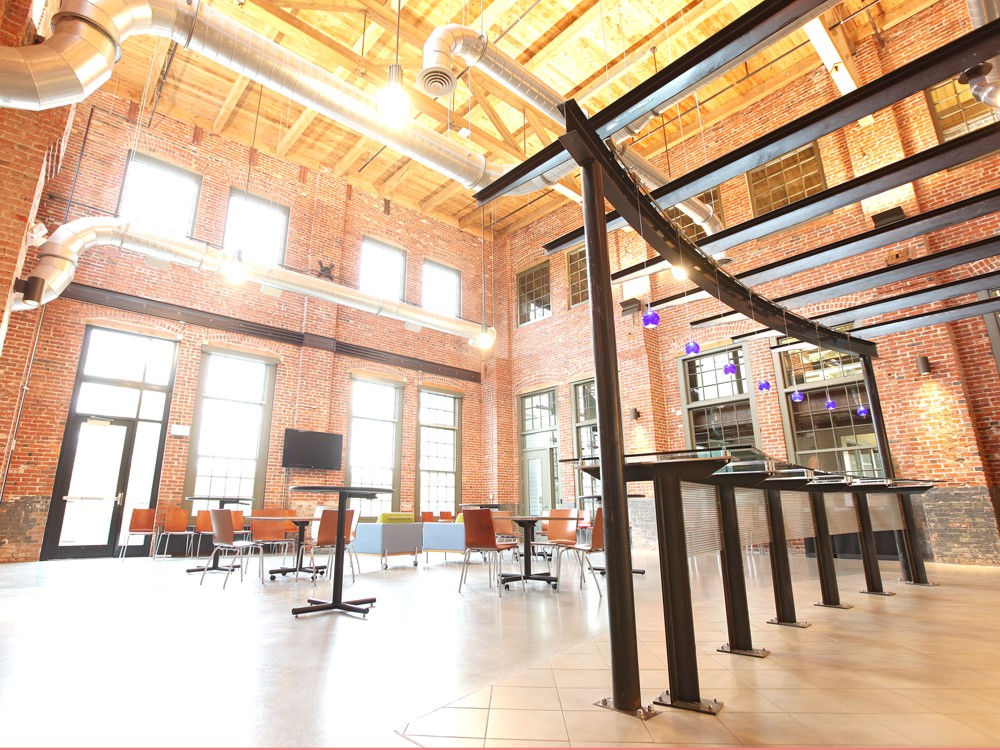

It took $20 million to buy the property and renovate it, most of that to add high-tech upgrades and modern amenities. The building itself — dense structural masonry with massive timber trusses holding the roof — was still stout after a century. “We only had to replace one truss,” Pearman-Gillman says.

A recent analysis by the National Trust estimates that it can take 80 years to recoup the energy it takes to demolish an old building, let alone build a new one.

That’s where McKinstry — a large Seattle developer and engineering firm that focuses on the entire life of buildings — saw a lot of value in an old, sturdy building. “We’re hardcore engineers,” Pearman-Gillman says. “We have this passion for taking waste out of the system and this passion for saving the planet. Knowing that we can do better.”

Those values made the SIERR project more expensive at the outset, but Pearman-Gillman says the costs also challenged the company to recycle and rework as many materials as possible. The company works from what is called a triple bottom line. Not just worrying about profit, but also the effect on people and on the planet. “It’s more expensive, but we weren’t building a 20- or 30-year building, which is what most buildings are now,” she says. “We were making a 100-year analysis.”

Spokane has a history of that sort of development. That’s partly what drew next week’s National Preservation Conference to Spokane. Spokane is the smallest city to ever host the conference, but Barbara Pahl, director of the West Coast field office for the National Trust for Historic Preservation, says the city deserves its place.

“Preservation should make us think about what buildings are we going to bring with us into the future,” she says. “We can’t take everything, but we don’t want want to take nothing. Spokane has had as good a [preservation] record as any city and maybe better than most.”

Projects like the SIERR project are vital, adds Paul Mann, who holds a number of positions on local and national preservation boards, and is the co-chair of the National Preservation Conference.

Half of the buildings in Spokane’s core are historic, Mann says, and most of them are still viable. What it takes, though, is vision. It’s easy to see the value and weep at the potential loss of a landmark like the Davenport Hotel, he says. It’s harder to see the history in buildings like the Jensen-Byrd warehouse, which was set to be demolished for student housing before outcry caused the developers to scrap their plans.

Mann tells a story of standing in Washington Water Power’s old Central Steam Plant in 1996 when Ron Wells and Avista announced plans to redevelop the space and the adjacent Seehorn-Lang building into a commercial, retail and entertainment center.

“It was cold and dirty, and there was a frozen waterfall in the basement,” Mann remembers. “There was enough pigeon guano to fertilize the Palouse for years.”

Mann had known Wells for years, and respected the preservation and restoration his company, Wells and Co., had done to dozens of buildings. Still, Mann thought, “Have you lost your mind?”

Wells had vision, though, Mann says, and Steam Plant Square went on to win the the prestigious Preservation Honor Award from the National Trust for Historic Preservation in 2001. This year, McKinstry’s SIERR Building is up for the same award, which will be announced next week at the conference.

“We think of ourselves as innovators,” Pearman-Gillman says, “and so we always want people interacting with our employees, pushing us, and then creating a building that facilitates that interaction.”

Old warehouses matter as much as old theaters, Mann adds. “In some ways,” he says, “the Jensen-Byrd means more [to Spokane] than the Davenport or the Fox.” The iconic hotel and theater were places for Spokane’s elite. Buildings like the Jensen-Byrd were the blue-collar economic engines of this town. The SIERR kept our public transit system functioning. “This is about saving aspects of our whole society,” Mann says.

But Pahl stresses that preservation is no longer about creating museums out of beautiful old Victorian homes. It’s about giving old buildings new purpose. “Within minutes without bees, a beehive disintegrates,” Pahl says. Buildings take longer to crumble, but the idea is the same. “They need life in them.”