Tuesday, October 21, 2014

The CW is an easy network to make fun of. It’s often light-hearted soap-operatic fare, full of OMG and the occasional WTF. This, after all, was the network that gave us Gossip Girl, a show that ended with the reveal that Gossip Girl was actually Gossip Boy.

And yet, their superhero shows, Arrow and The Flash, are so much better than those on other networks, like Gotham and Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D.

Some of this is because both come mostly free of baggage for the average viewer. Most people vaguely aware of comic books are familiar with The Flash (he’s that speedy dude, right?), but he hasn’t been a pervasive part of the pop cultural world the way Batman, Superman, Spider-Man and the X-Men have been pounded into our psyche. Green Arrow is even more obscure, though he’s had roles on Smallville and animated shows like Batman: The Brave and the Bold.

This alleviates the terrible burden of expectations. Arrow (Wednesdays, 8 pm) takes place in Starling City and The Flash (Tuesdays, 8 pm) in Central City, not in Gotham or Metropolis. We don’t have to constantly question why Superman and Batman aren’t constantly part of plot lines, or why Iron Man and Thor aren’t constantly showing up to save them. Viewers don’t have to compare Grant Gustin’s performance as Barry Allen to, say, the performance of Val Kilmer, Adam West and Christian Bale.

In fact, The Flash had the freedom to somewhat reinvent the Flash origin story. (Particle Accelerators were hard to come by back in 1956. A lightning bolt and chemical spill had to suffice.)

But there’s a deeper lesson in these two shows, that very much can be credited to the CW. At its core, they’re CW shows, with all their beautiful people, love triangles, fancy clothes, nice cars and plot twists. The DNA of shows like Gossip Girl, in other words, has been spliced with the superhero's ethos.

CW has taken genres it already does well and dressed it up in superhero tights. A superhero show can’t just be about superpowers, just like Friday Night Lights would have failed if it were only about football. Superhero fights can barely sustain a three-hour movie, much less a TV season with a lower budget.

So on Arrow, Oliver Queen disguises himself as a rich, entitled douche to better keep his heroism secret. But this, of course, allows Arrow to spin out rich, entitled subplots that are interesting enough on their own. Arrow draws a lot on Count of Monte Cristo, essentially the original Batman story.

The Flash is show that, ironically, captures the light-hearted Marvel movie tone far better than Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. It has a Peter Parker sense of "Gee whiz!" and fun that Gotham never tries for and S.H.I.E.L.D struggles to balance with genuine stakes. Allen is young and gung-ho: The CW knows all about writing young and gung-ho.

A good test for any superhero show: Would this be an interesting show without any superpowers or action scenes? Is there anything of substance behind the mask? Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. is barely interesting with superpower action scenes. But you could take the Flashiness out of The Flash and have a decent twenty-something drama, or extract the Green Arrow from Arrow and have a decent one-percenter soap opera. Lengthy side plots in Arrow have nothing to do with the Green Arrow, but plenty to do with the drama between Oliver Queen and his friends.

In a way, it’s no surprise the CW manages this challenge. After all, the CW is the heir to the WB, the network that launched Buffy The Vampire Slayer, the Joss Whedon show that deftly grafted high school drama and angst onto supernatural battles. Buffy’s worried about slaying vampires, yes, but she’s also worried about prom and graduation. (Partly, to be fair, because prom is besieged by demon dogs and the graduation speaker turns into a giant snake.)

Smallville ran a full 10 seasons, partly by withholding a lot of the superhero mythos (flight, for example) for a very long time. But it also strapped it all on a backbone of teen drama, which surely helped. Soapy plot twists are far cheaper than flashy special effects.

That doesn’t mean that every superhero show needs to be a teen drama. If Gotham was truly able to turn into a more subtle corrupt-cop show, in the style of The Chicago Code, it could be sustainable. For now, however, it has cops standing around essentially saying “Man, we are so crazy corrupt, ain’t we?” Corruption is subtle and pervasive. It’s about culture, and Gotham struggles to do anything subtle.

ABC’s No Ordinary Family tried to turn family drama into its superhero show, but its family dynamics were so dull and pedestrian it didn’t matter. Give the folks on Parenthood superpowers (Max already has superhuman tenacity on Skittles-related matters) on the other hand, and that would be interesting. And is there any doubt that Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. would be better if it were run by Shonda Rhimes? (Rhimes is maybe the one show-runner who could write a version of Wonder Woman I’d watch.)

All of this, of course, is to say the secret to having a good superhero TV show is to have a good TV show, then just add superheroes. Even Batman can’t save leaden dialogue or dull characters.

Tags: CW , Gotham , Flash , Arrow , Agents of Shield , TV , Image

Friday, October 3, 2014

How To Get Away With Murder, despite nearly every character acting the sneering villains the college comedy slackers would humble with a crazy prank, is shaping up to be one of the most enjoyable new shows. It’s got that shamelessly dramatic dialogue, monologues and plot-twists of the best guilty pleasures.

But almost immediately, it has a big flaw stuck into the very structure of the show: It gives us brief “flash-forwards” into a scene where the characters appear to be hurriedly covering up a murder.

The flash-forward gimmick is hardly a new one.

How To Get Away With Murder’s device is an almost exact ripoff of one of the worst parts of another legal thriller, Damages. That show parceled out the narrative in the present with brief glimpses of the future — horrible things happening to an ambitious legal mind due to her involvement with a take-no-prisoners female mentor. (How To Get Away With Murder distinguishes itself by giving us glimpses of horrible things happening to multiple ambitious legal minds due to their involvement with a take-no-prisoners female mentor.)

It’s a device that’s been used in shows like Lost, Breaking Bad, and How I Met Your Mother. And it hurt every one of them.

Heck, there was even a television show called FlashForward that made this the entire premise – that everyone on earth sees a vision of themselves from the future — and it buckled and collapsed under the strain almost instantly.

The temptation for a writer to put a flash-forward in a pilot is understandable. It’s a promise: This is how crazy things will get. It’s supposed to be like your friend saying, "Hey, stick with it, the show gets really good around episode 22."

But flash-forwards ultimately are more like skeevy payday loan operations: They borrow interesting narrative from the future to spend in the present. And the interest rates are downright predatory.

To expand on that: One of the most enjoyable parts of watching TV is asking two fundamental questions: 1) What is happening now? 2) What will happen next? Yet a flashforward spoils the answer to #2 and makes the answer to #1 feel irrelevant. Both questions are replaced with “How does the story get from A to B?” (Or A to Z.) That’s not a mystery or an adventure. That’s a MapQuest printout.

A flashback is problematic because it kills narrative momentum by taking us out of the present. Why would I care about what happened six months ago? I want to know what’s happening now. But flash-forwards turn almost the entire show into one giant flashback. It cheapens what’s happening in the present by showing us the consequences.

Sometimes those flash-forwards are lies: They use unreliable narration, deceptive editing or trick camera angles to pretend something will happen when it won’t. But that breaks the trust between viewer and show, which greatly harms future seasons.

How I Met Your Mother had to bend over backwards to try to fulfill the many promises the show had made about the future and still surprise the audience. The result had the fans angry and revolting.

Other times, the flash-forwards are the exact truth, creating expectations difficult to fulfill: The reveal of Lost’s flash-forwards made for an iconic moment, for example, but the story struggled to fill in the gaps in a logical, satisfying way.

Mind you: A flash-forward can work brilliantly in long-form non-fiction journalism. Even novels, to a certain extent, can benefit from this sort of structure.

But a serialized TV drama is not a novel or long-form non-fiction. It is a serialized TV drama – and one of its biggest strengths should be its agility. The story is a living, breathing thing that can veer off in wonderfully surprising directions. A plotline that’s not working can be excised, a character can be killed off, a more interesting thread can be pulled. Most of the time, it’s not the vision of one mind, it’s a room of writers. Epiphany can strike and transform a show at any time.

Actors quit. Actors die. Ratings fall. Writers change their minds.

In some cases, a flash-forward can work within a single episode. A Breaking Bad episode opens with the serial image of bullet shells on the hood of a car, bouncing as hydraulics send the car up-and-down. It’s a tease more than a spoiler. It’s a poetic image that hooks and intrigues.

But Breaking Bad stumbled when it tried to create season-long flash-forwards. It famously began its 5th season with a bearded Walter White opening up his trunk to reveal a massive machine gun. At the time the writers had no idea what it would be used for.

The result was the worst of both worlds: The constraints of a perfectly planned show and the lack of foresight of an improvised one. Partly as a consequence, the finale to one of TV’s best shows of all time was, ultimately, disappointing.

How To Get Away With Murder doesn’t aspire to Breaking Bad’s greatness. But it wants to be surprising, fun and fast-paced – and flash-forwards make every one of those goals more difficult.

Wednesday, October 1, 2014

Washington Grown, a 13-episode television series highlighting local farms, premieres its second season with a preview party tonight at 5:30 pm at the Magic Lantern.

The show was created by Spokane film studio North by Northwest, in partnership with the Washington Farmers and Ranchers. The latter is an organization that helps promote the locally owned farmers in our state.

A new "food journey" is chronicled in each episode, beginning at a Washington farm where an ingredient or product is grown, and following the goods as they travel to a local restaurant to be prepared. Spokane restaurants Sante, Luna and the Steam Plant are among those to be featured in season two.

During the preview, the Magic Lantern is serving light hors d'oeuvres and drinks, because what's the point of watching a food show without snacks?

Northwest Cable News airs Washington Grown on Sundays at noon and 8:30 pm beginning this week. Episodes can also be streamed online the following Monday after its original airing at wagrown.com. Also on the site, find recipes for many of the featured ingredients and restaurants on the show. Several caught our eye — including Dick's fries and Sweet Frostings' cupcakes.

Tags: Culture , Food , Washington Grown , North by Northwest , TV , Image , Video

Thursday, September 25, 2014

Tonight, How To Get Away With Murder launches, along with new seasons of Grey’s Anatomy and Scandal. The same woman, arguably one of the most powerful showrunners on television, has her hands in all three: Shonda Rhimes.

Last week, that Rhimes got a lot of unanticipated press when New York Times TV critic Alessandra Stanley began her column on Rhimes with a line, “When Shonda Rhimes writes her autobiography, it should be called 'How to Get Away With Being an Angry Black Woman.'” She continued to talk about how, in her show, Rhimes rises above that stereotype, reinvents and reclaims it.

Numerous critics, viewers and even Rhimes herself cried foul, concentrating on how the column was racially insensitive.

But it wasn’t bad TV criticism just because it was racially insensitive. It was racially insensitive because it was bad TV criticism. (New York Times TV critics do not have the strongest record.)

In other words, a show like Key and Peele channels and subverts racial stereotypes every week, and there would be nothing wrong about pointing that out (including the stereotype of the Angry Black Man.)

But here, Stanley got Rhimes completely wrong. Anger and race isn’t what makes her interesting. No, she’s interesting for the way she deals with the entire range of emotions with characters of all races, genders and sexual orientations.

That Stanley honed in on single stereotype that did not represent the the thrust of her work – that’s what was racially offensive.

Yes, Rhimes' shows sometimes thrive on anger. But that’s just one color in her palette that she uses to paint bright, vivid, sometimes absurd and surreal TV shows.

I often refer to them as "Strong Woman Crying" shows, but that isn't meant to be an insult. In many shows, Strong Woman is a synonym for Dull Woman. She understands that men and women can be strong and competent, but also weak, brittle, ill-tempered and foolish. And that is where drama often comes from. At times it drags the show down, makes it repetitive and exhausting. Other times, it invigorates the show, injects it with an unhinged kind of energy.

It’s been a long time since I’ve watched Grey’s Anatomy (appropriately timed trivia fact: Katherine Heigl’s Izzie Stevens character was a graduate of the University of Washington school of medicine.) But from what I remember of Grey’s, it was infused with the same sort of wonderful over-the-top style as Scandal.

Yes, they all have lots of plot twists and life-or-death moments, but that’s not what invigorates them. It’s this overpowering sense of momentum and emotion and desire that sends characters hurtling in wild directions.

It’s melodrama, yes. It’s soap opera, yes. But neither of those things are bad things when they’re executed skillfully. And if nothing else, Rhimes knows what she’s doing.

Stylistically, she’s maybe the closest match to West Wing creator Aaron Sorkin, with her tendency to have characters deliver hyper-articulate barnburner speeches at the drop of a hat. But where the passion in Sorkin’s comes through wonkery – a Great Man standing before a podium and firing off rat-a-tat-tat statistics and studies to decimate his doofus of an opponent – Rhimes' monologues are almost entirely about emotional desire. They’re the equivalent of an “I Want” song from a musical: One character stands before the other, and the words just come spilling out with rhythms and beats and crescendos.

These are the sorts of monologues that we fantasize about delivering to the people we care about most, telling them why we love them or telling them why we hate them. It’s a pep talk, telling them that the whole world is counting on them. It’s the tell-off speech, telling them they screwed up royally and it will cost them every single thing they’ve ever wanted. It's ultimatum as music. These are the climactic epic monologues that most movies get one of. Rhimes throws them out in nearly every single episode.

(Life lesson: In my experience, Rhimes-style Choose Me monologues are sadly not nearly as effective in romantic relationships as in real life.)

And it’s here that actors like Jeff Perry get a chance to show us some of TV’s best acting. It’s here where politically infused shows like 24 and House of Cards could take a lesson. Political drama isn’t about talking points. It’s about the motivations and desire behind it all.

A show like The Good Wife does a much better job at portraying actual adult relationships, where things like duty and family actually matter, where the right choice often means repressing all those emotions. But, like musicals, like poetry, the unrealism in Scandal is there to speak to a deeper reality, to how feelings really feel, stripped away from all that sense and rationality.

So, no, her characters don’t act like adults. But neither do our hearts and minds and guts. She captures that uncivilized adolescent id inside us all. We humans are whiny. We humans are angry. We’re overcome with desire and depression and anxiety and burning passion and self-destruction, though we manage to make the right choices in the end. Most of us. Usually.

Rhimes’ characters mostly don’t. Even a character like Olivia Pope, a paragon of intellect and competence, can’t stop her desires from sabotaging her life in every way.

That isn’t exclusively a female thing, by the way. Practically every character in Scandal follows his or her heart, and other body parts, into stupid, stupid places. But that’s the beauty of it. That’s the fun, and insight, of visiting that what-if world of unrealistic plot twists and unrealistic speeches.

It has nothing to do with being angry. It has nothing to do with being black. It has everything to do with knowing what it’s like, in our most heightened, insane moments, to be human.

Friday, September 12, 2014

The show debuts tonight at 10 pm on SyFy, and if you haven't heard, it's about zombies and people who try desperately not to either become a zombie or get eaten by zombies. So yeah, it's a zombie show. I wrote a little about how it wasn't, ya know, horrible, in this week's paper. I actually used the phrase "pretty good" — which I now regret having watched the show a second time. I'd like to downgrade my assessment to "not that bad."

But we needed to focus-group this thing.

The screening was interrupted frequently by people asking questions like, "Does every zombie show have to exist in a world where none of the characters have ever seen a zombie show?" and waxing philosophical with observations like, "This is the part where man becomes more of a threat than the zombies." There was also a lot of laughter, which we're still not sure the Z Nation producers were looking for.

THE WALKING DEAD COMPARISONS

One aspect I can appreciate is that it doesn't require dealing with as much, um, "thinking" or "feeling" as the inevitable comparison partner The Walking Dead. As memory serves, even the Dead pilot evoked actually caring about the characters, while Z Nation seems like it's going to be all about the action. Kill them zombies! Get Murphy to California! Watch out for that infected baby! I really hope it continues that way, because efforts to make the viewer care instead of just enjoy for its popcorn-cheesiness probably won't go so well given the low caliber of the acting, and the ridiculous (lack of) special effects. Another bad note — having DJ Qualls turn into Mr. Pump Up the Volume DJ at the end. Yikes! No. More baby zombies. Less DJ Qualls. And no thinking, dammit! (Dan "The New Guy" Nailen)

Z Nation isn't really doing anything new, which might not be bad. Zombies ascended on the popularity of straight-forward horror classics like Night of the Living Dead or Evil Dead — stripped-down, gore-splattered, who-will-die-next survival thrillers. Z Nation seems to serialize that concept. Sure the premiere has pacing problems, laughable dialogue ("I hate moral dilemmas!") and some stereotypical characters, but it moves quickly and keeps the zombie slaughter coming. Hopefully, the series can dial in the tone, which seems to ping-pong from serious drama to camp a little too liberally. If so, it might easily replace your Saturday night horror-flick marathon. (Jacob "Thunderbeard" Jones)

WEIGHING THE GOOD AND THE BAD

Pros: cool old guy, no one yelling "Carl!," zombies getting their entire brain shot out of their head, zombies getting hit by a truck, school bus full of kid zombies, lake zombies, zombie baby. Cons: All of the dialogue, WHY ARE THEY WASTING SO MUCH AMMO?, no sharks. (Heidi "Save the Bullets" Groover)

On the second time around, I thought I'd recognize more of Spokane. I also thought there would be more sweaty sexy guys, because television has taught me they make the best zombie killers. (Mike "Father of Zombie Baby" Bookey)

THOUGHTS ABOUT ZOMBIE BABIES

Zombie babies will forever haunt my dreams. (Deanna "Sasquatch" Pan)

Based on the order of events, we assume baby Z was infected during the scene where one of our human heroes fights off another perfectly-timed zombie-after-zombie filing into the room. There on the floor sits the baby (still human) in his carseat as zombies run around dying everywhere. It’s important to note the age of this infant is pre-walking stage. But when the baby tragically becomes infected, he suddenly has immediate abilities to walk, run, and zip all over the place like a freaky demon of nightmares. We all seemed too enthralled by its mere existence to care, but it seems Z Nation has no cut- and-dry rules when it comes to zombie behavior, and as a zombie-themed show that might bother you, too. (Chey "Whiskers" Scott)

DANIEL WALTERS PROVIDES A SERIOUS LOOK AT THE SHOW, BECAUSE HE'S A REAL TV CRITIC

Here’s the problem with Z Nation. It’s not bad enough to be so-bad-it’s-good, and not good enough to be so-good-it’s-decent. In other words, you can’t watch Z Nation in the same fun way you watch, say, Sharknado. There won’t be crowds on Twitter hate-watching Z Nation, mocking every mockable moment.

That’s not to say there aren’t mockable moments. There are are a quite a few, if you’re in a RiffTrax sort of mood, but overall, the essence of Z Nation isn’t cheese. It’s more derivative if anything, pumping out the darkness and dreariness of Walking Dead with none of the craft that makes that show occasionally tense and suspenseful. So when the corny moments do come – there’s a zombie Bride of Chucky scene that’s sublime – it’s something of a relief.

While recognizable actors Harold Perrineau (the Michael that yells WAAAAAALT all the time on Lost) and DJ Qualls (the scrawny dude from Road Trip) do make appearances, both are miscast. Perrineau is a fine actor, but pretty much any of the other actors, including Qualls and the tiny infant, would be more believable as a badass Delta Force agent than Perrineau.

And Qualls just doesn’t display the weirdness that his character needs. As an actor, he’s capable of that weirdness. As a show, Z Nation is, too – it just needs a little more of it. (Daniel "Don't Give Me a Nickname" Walters)

NOW MORE ZOMBIE BABY!

Monday, September 8, 2014

There was a time when Sons of Anarchy, the gritty biker gang drama, flirted with greatness.

But today, with its 7th and final season premiering next Tuesday, that greatness is a distant memory. Instead, the most enjoyable thing lately about Sons of Anarchy is unpacking its succession of flaws: The dry exposition. The boring lead. The lackluster action scenes. The tendency to change the status quo far, far too late. Everything having to do with Ireland.

But lately, there’s been another problem, one once practically unheard of on television: Even at 42 minutes, Sons of Anarchy could be a slog. And yet, it often insisted on stretching that slog out even further. Nearly every single episode is supersized, running far beyond the typical TV drama running time.

Two of the 13 episodes in Season 5 were an hour long, and an additional three stretched 46 minutes or longer. In Season 6, the problem was even worse: The shortest episode was 52 minutes, and nine of them topped an hour. That meant more time for dreary musical montages, more check-ins with every tertiary character, more repetitive conversations where characters state their motivations and frustrations outright.

The supersized TV episode used to be a rare phenomenon, a gift for fans saved for series finales or holiday specials. But lately, networks like FX have given their show-runners far more free reign to experiment. And in the same way word counts no longer apply to the infinite expanses of the internet, Netflix has given writers opportunity to bust through length restrictions at their whims.

But just because an article can be 10,000 words doesn’t mean it should be. Remember the hour-long episodes of The Office, bloated and dull? Or the interminable early episodes of the Netflix-season of Arrested Development?

Or consider BBC’s Sherlock’s, where the extra-long episodes are just an excuse to meander down fitfully amusing rabbit trails or stage zany slapstick scenes with bouncy music.

Sherlock suffers two ways: It’s too short and it’s too long. Each season has a scant three episodes, but each of them last 90 minutes a piece. A typical procedural mystery shows often struggle to fill 42 minutes with interesting twists and character insights. And Sherlock Holmes basically invented the typical procedural mystery show.

Sherlock is not exactly CSI: Baker Street, but the extra length doesn't improve the show. Instead, it just contributes to lumpy, unevenly constructed episodes.

Sherlock frames one episode’s mystery nearly entirely through a boorish wedding toast given by Sherlock Holmes to dear Watson. The central conceit is that of course Sherlock would hijack a toast to make it about him. Then, in an attempt at sentimentality, Sherlock explains it is precisely the fact that Watson tolerates someone like Sherlock as a friend that makes Watson a wonderful human being.

Except, the sheer length of the episode drags the toast, and the story it frames, out to a length where Sherlock goes from lovably socially awkward to downright sociopathic at his best friend's wedding.

Granted, 90 minutes is positively sleek by movie standards. Yet television typically has different demands for its narrative structure than a movie. TV’s domain, particularly serialized TV like Sons of Anarchy, is the long, fat middle of stories.

TV writers have trained for the three-act half-hour sitcom and the five-or-four-act drama – give them more minutes and that structure may suddenly not apply. Supersizing an episode is like asking an 800-meter track star to take up the steeplechase: You expect them to occasionally stumble and get winded. It doesn’t mean they can’t do a fine job. But it’s not their specialty.

The secret, I think, to pulling off a longer episode, is not necessarily through a higher quantity of scenes or an increase in subplots, but through longer, more focused scenes. Many shows flit back and forth between characters, through two minute or three minute check-ins. But often the best moments are when the shows allow themselves to truly slow down, to savor the moment. Witness one of my favorite scenes of Game of Thrones this year, where Oberyn Martell, who hates the Lannister family like few others, promises to risk his life to defend Tyrion Lannister. It’s a moment that could easily have been shorter or faster-paced or told through flashbacks, but it resists that urge, focuses on the quiet and the character.

Supersized episodes, theoretically, could be used for more of these scenes. (Game of Thrones certainly benefits whenever it focuses.) Shows could use their extra running time to go deeper instead of broader or more redundant. In Treatment, the innovative HBO drama set almost entirely in therapy sessions, thrives with the slightly longer episode lengths. And that drama typically only consisted of one 30-minute scene per episode, with only two people talking.

The trick is having the interesting characters, motivations, and stories to fill those longer scenes. The fact that Sons of Anarchy often doesn’t have those – well, that’s a bigger problem entirely.

Tags: FX , Sherlock , Sons of Anarchy , TV , Image

Thursday, August 28, 2014

For four years, Doctor Who has been pure fan fiction.

That’s not a pejorative, it’s simply an accurate description: The show’s current showrunner, Steven Moffat, was once a little chubby curly-haired kid watching the old Doctor Who series and reading Doctor Who paperbacks.

And, in a fairy-tale happy ending, that little boy grew up and took reins of the show he loved so much.

Doctor Who, if you haven’t heard, is a show about a zany British-accented Time Lord, who takes his “companions” (usually an attractive female) on all sorts of adventures. Moffat, a writer on the show (and writer of the Emmy Award-winning Sherlock) replaced Russell T. Davies as Doctor Who’s head showrunner in 2010. Most people were excited. After all, Moffat had written some of the show’s best episodes.

But in the last few years, Moffat’s come under fire for what they see as a decline of Doctor Who. Critics say he’s sexist, that he’s too obsessed with puzzle-box plotting, that he hits his themes too often, that he’s made the show too big and too messy.

Taken individually, many of the points they make are good ones, but in trying to say that Moffat has hurt the show as a whole, they seem to forget how many awful moments there were during the Davies era. The worst, worst, worst of Doctor Who came under Davies: The two-parter with the farting aliens? Written by Davies. The terrible episode that ends with the implication of a character getting oral sex from a paving stone? Written by Davies. And while he didn’t write it, he pushed the main plot-points for “Fear Her,” the cringe-worthy episode with drawings that come alive.

Moffat’s seasons have been uneven, sure: But never so bad as Davies’ worst moments.

By contrast, nearly every great episode from the Davies era was written by Moffat. He was the one coming up with all the best ideas: Carnivorous shadows. Stone angels that murder by touch, but only move when you blink. A medical nanobot swarm that re-forms human faces into the visages of gas masks. In fact, sometimes Moffat’s weakness is too many good ideas. He tries to shove a dozen sci-fi concepts into single episodes and crowds out the impact of any of them. Even when Moffat became showrunner, he delivered, by far, the best Christmas serial of the modern era, using time-travel as an elegant way to deconstruct and reimagine Dickens’ A Christmas Carol. Even the weakest episodes of his tenure have had great moments.

Look at this beautiful monologue, where The Doctor tells off a God the size of a sun, or this one, where he sums up the whole show by unreeling the scope and danger of the universe to a beleaguered dad. Both are from mediocre episodes (written by other writers during Moffat’s run) but they contain some of my favorite scenes.

Frankly, Moffat is just more creative. Davies relied on pure unimaginative scale to create stakes in his season finales, flooding Earth with a thousand Daleks or a million Cybermen, or a million Toclafane. Davies created impossible situations then easily resolved them with a magical button press, a flurry of techno-babble, or the gauzy power of love.

Moffat, for the most part, went a far more complicated route: He plants the seeds of the villains’ defeats in his finales far before he even faces them. The success of this tactic has been uneven, but it’s far more ambitious and fascinating than anything his predecessor attempted. Even the chaos and frantic nature of the show feel like they reflect the character of the show’s central figure.

Doctor Who is a show about the wonder and terror of time as well the wonder and terror of space. Moffat understands that, using time travel as a tool to explore the horror of old age and loneliness, to examine the redemptive power, not of love, but of memory. That’s a rabbit hole worthy of exploring.

One accusation does seem valid: His major female characters — River Song, Amy Pond, Clara Oswald — all feel cut from the same cloth. Remove the actresses performances from the equation and the writing for them often feels identical.

But Moffat’s writing of his companions, flirtatious and prone to sexually-charged banter, seem far less sexist than Davies’ writing of Rose Tyler, the companion who spent much of her time desperately mooning over the doctor. Some critics have accused Moffat’s female characters of too often playing damsels in distress. But Pond is much more assertive and foregrounded than her husband. Both Pond and her husband are damsels in distress at times, yet both get to be the shiny-armored knights riding to the other’s rescue.

Moffat is an uneven writer, sure. But Doctor Who has always been a wonderfully uneven show, all the way back in the days of black-and-white monsters with visible zippers.

Tags: Doctor Who , BBC , TV , Image

Friday, August 22, 2014

It’s maddening that, with an American city ablaze with protests and police brutality, our national leaders think it’s OK to just take a vacation.

I’m speaking, of course, of Jon Stewart and Stephen Colbert, who took these past two weeks off when America has needed their outrage and comedy the most.

And so our nation turns its lonely eyes to you, John Oliver. Thankfully, on Sunday, Oliver delivered:

Oliver only has a handful of episodes of his new HBO show, Last Week Tonight, under his belt. But in at least one way – the 15-or-so minute rant – the former Daily Show correspondent has bested his former boss.

Nearly every Monday, HBO releases Oliver’s 15-minute exploration of an outrage on YouTube. And nearly every Monday, it’s dutifully shared and hyperbolically celebrated by numerous news outlets.

Here’s why Oliver’s rants work so well:

Time

During HBO shows, there are no commercials. But few HBO shows (In Treatment comes to mind) regularly take advantage of the freedom that provides. Oliver does.

He has eight extra minutes to work with, isn’t saddled with the need to bring on a celebrity to talk about her latest movie and doesn’t have to stop every 10 minutes to let the network sell blenders or promote Tosh.0

In practice, the Daily Show and Colbert Report work more like daily papers: Shorter stories and more of them. But Last Week Tonight looks more like an alt-weekly — finding big stories few people are talking about and really exploring their ramifications. The deep dives are made possible, not just by the additional screen time, but by the fact that Oliver only has to do one show a week.

Topics

While his Ferguson comments have been widely praised, I believe Oliver's even better when he tackles more underreported subjects – like the scumminess of the soccer organization FIFA, the impact of Net Neutrality legislation, the collapse of the wall between news and advertising, the shady ethics of Doctor Oz, and the predatory tactics of payday loan organizations.

The Daily Show has its moments of unpacking undercovered and complex topics, exposing financial scandals or huge problems with the veteran’s administration bureaucracy. But because of the sheer quantity of material the Daily Show has to produce, they fall too easily back on montages of Fox News idiocy or political hypocrisy.

Tone

Obviously, Colbert, Stewart and Oliver focus on similar themes. But it’s Oliver’s tone that makes the difference. He’s not spittle-flecked furious like occasional Daily Show contributor Lewis Black and he’s not screw-it-all cynical like Stewart, and not satirically self-confident like Colbert.

Instead, his rants seem almost happy. And, that, oddly enough, makes them more effective. He’s pointing and says, “Check this out! This is so absolutely, mind-blowingly horrible, you’ve just got to let out a little chuckle. Ha ha! Everything’s terrible!”

Maybe his best moment is this one, where to soaring music, he summons the legion of the internet’s worst denizens, the sort who unleash vile rants without any of the irony or sophistication of Oliver’s rants, to flood the FCC with their complaints about net neutrality.

For once in your life, we need you channel that anger, that badly spelled bile, that you normally reserve for unforgivable attacks on actresses you disagree with, or politicians you disagree with, or photos of your ex-girlfriend getting on with her life, or non-white actors being cast as fictional characters. And I’m talking to you, RonPaulFan2016. And you OneDirection4Ever, and I’m talking to you, OneDirectionSuxBalls. We need you get out there, and once in your life, focus your indiscriminate rage in a useful direction, seize your moment my lovely trolls! Turn on caps lock and fly my pretties! Fly!”

With a different tone, one less gleeful, you could see the comedy falling flat. Instead, it comes off as nearly inspirational. And it worked: Those trolls broke the FCC’s website. Jon Oliver, clearly, has just as much power as Colbert or Stewart to inspire the masses to do his bidding.

Tags: Jon Oliver , Last Week Tonight , Daily Show , TV , Image , Video

Wednesday, July 30, 2014

We've been wondering what this zombie show that's been filming in Spokane all summer is going to look like. And it sounds like tonight we might finally get a look.

During the world premier of Sharknado 2 tonight on the Syfy channel, there's going to be a preview of Z Nation, which features real-life Spokanites as zombies.

Z Nation is about a group of survivors of a plague that turned most of the world into zombies who are trying to get across the country to save the world (or something like that), is produced by the same company, The Asylum, that made the Sharknado movies.

Sharknado 2, like its predecessor, is about a tornado full of sharks that makes landfall, causing massive devastation. It's some seriously high-minded stuff. As stupid as it sounds (and as stupid as it is — I've seen it), the Sharknado movies are oddly popular, mostly because they are comprised of ridiculous scenes like these. But it's not beneath the New Yorker profiling the making of the sequel.

You can catch this nonsense tonight at 9 pm on SyFy, and enjoy flying shark after flying shark until the sneak peek of Z Nation finally quells at least a bit of the curiosity that's been building inside so many of us this summer.

UPDATE: Here's the trailer:

Thursday, July 24, 2014

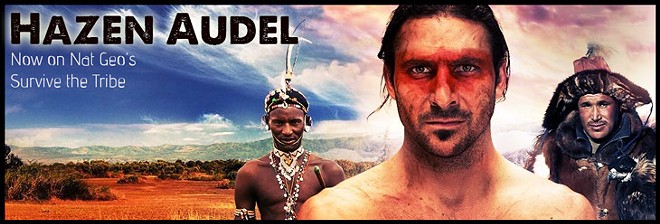

In this week's issue we profile Hazen Audel, who's starring in National Geographic Channel's new reality show Survive the Tribe. Audel taught art and science at Ferris High School up until last year. Our profile on Audel describes his more recent adventures running a guiding business in the Amazon jungle, along with other stories on how he's filled three passports from his travels since 1998. On the new show, debuting tonight at 9 pm, Audel spends a week or more learning about the culture of each indigenous tribe he visits and, as the title suggests, tries to adapt and survive.

Tags: Hazen Audel , TV , Culture , Arts & Culture , Image , Video