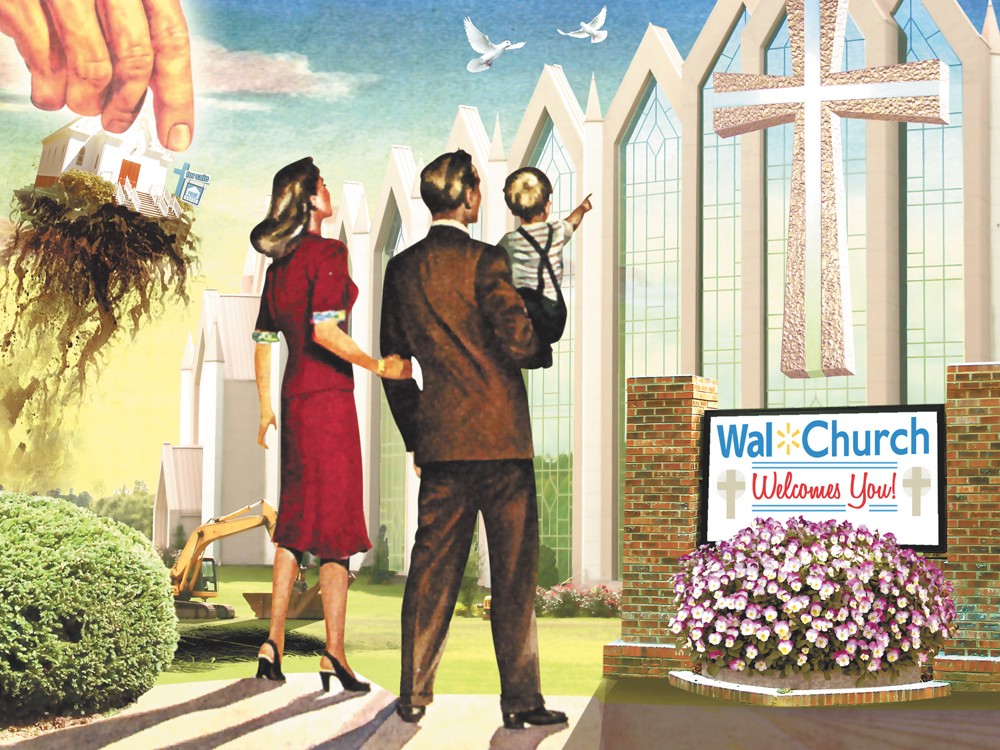

We’ve heard stories, for years, about big-box retailers like Wal-Mart coming into town and pushing out the sweet, smalltown, mom-and-pop businesses that had been operating there for years. We can think of hardware stores, markets and book shops that have been shuttered because they couldn’t compete with a corporate behemoth.

But what about churches? There’s a growing body of research on the phenomenon known as the “megachurch” — large churches, usually evangelical in nature, with over 2,000 weekly attendants and, sometimes, amusement-park-like amenities: shops, athletic facilities, even water parks, in some cases.

Such churches have been on the rise in recent years. Their numbers almost doubled between 1990 and 2000, and they seem to be driving a concentration of Christian adherents into bigger and bigger congregations. One study of a megachurch in Atlanta showed that its congregation was bigger than the population of the town the church was located in.

So what happens to all the little churches in town when such a Goliath rolls in? That’s what Whitworth University sociology professor Jason Wollschleger wanted to know.

“We really had two competing theories,” says Wollschleger, sitting in an office bedecked with student artwork of Jonestown cult leader Jim Jones. “The dominant one is that they’re like Wal-Marts — when they emerge, they put all the mom-and-pop businesses out of business.”

The other theory, he says, comes from economics — the idea that competition is good for everybody.

“And that fits really well with how megachurches like to spin themselves — that they’re bringing in the unchurched, that they’re not stealing members from other congregations.”

But neither of these theories seemed completely satisfying, he says, from the perspective of organizational ecology.

“[The theories] assume that a megachurch is going to affect everyone in the same way. [But] we understand that there’s different types of organizations that can be in similar fields, and that they can influence each other and work with different niches.”

So Wollschleger and a colleague from the City University of New York in Brooklyn broke out their maps. Focusing on two existing data sets, a constantly updated database of known megachurches and a county-level census of religious attendance across all Christian denominations between 1990 and 2000, they were able to map the growth of Christian churches across the country, coding them by denomination, and to categorize counties by those that contained a megachurch, those that adjoined a county with a megachurch, or those that were one county away from a county with a megachurch.

Here’s the key part of their results, which were published this year in the Review of Religious Research. The chart shows rates of change in attendance over the decade, broken down by denominaton and county type ("core counties" are those that contain a megachurch). To measure the rate of change, they calculated the number of people in each denomination per million people in the county (so as to compensate for the greatly varying sizes of counties), then subtracted the 1990 number from the 2000 number.

| Affiliation | U.S. Average | Non-Adjacent Counties | Adjacent Counties | Core Counties |

| Mainline Protestant | -85.87 | -86.40 | -81.48 | -27.69 |

| Catholic | -19.73 | -19.82 | -20.49 | -3.96 |

| Conservative Protestant | -43.64 | -42.68 | -81.33 | -14.57 |

| - Evangelical | 3.93 | 4.39 | -7.83 | -3.10 |

| - Pentecostal | -11.97 | -11.97 | -18.28 | -6.13 |

| - Fundamentalist | -10.85 | -9.58 | -47.79 | -3.77 |

The numbers confirmed two of their hypotheses.

The first was that having a megachurch in the same county was going to have a negative effect on congregations that occupied a similar religious niche. And indeed, Evangelical, Pentecostal and Fundamentalist churches in those counties were all slightly worse off, compared to the U.S. average.

| Affiliation | U.S. Average | Non-Adjacent Counties | Adjacent Counties | Core Counties |

| Mainline Protestant | -85.87 | -86.40 | -81.48 | -27.69 |

| Catholic | -19.73 | -19.82 | -20.49 | -3.96 |

| Conservative Protestant | -43.64 | -42.68 | -81.33 | -14.57 |

| - Evangelical | 3.93 | 4.39 | -7.83 | -3.10 |

| - Pentecostal | -11.97 | -11.97 | -18.28 | -6.13 |

| - Fundamentalist | -10.85 | -9.58 | -47.79 | -3.77 |

The second, surprising as it may seem, was that a megachurch moving into the county would actually benefit churches that were dissimilar — the theory being that the megachurch’s presence might spur competition and provide leaders of other kinds of churches with a kind of foil against which they could identify themselves.

“That’s one thing that we saw going back to the Wal- Mart analogy,” he says. “That [when] little stores could create a unique identity and offer something that Wal-Marts can’t … they do well.”

That bears out in the results. In the core counties, Mainline Protestants’ rate of decline is about one-third of the national average. For Catholics, it’s about one-fifth. So they seem to be benefitting.

| Affiliation | U.S. Average | Non-Adjacent Counties | Adjacent Counties | Core Counties |

| Mainline Protestant | -85.87 | -86.40 | -81.48 | -27.69 |

| Catholic | -19.73 | -19.82 | -20.49 | -3.96 |

| Conservative Protestant | -43.64 | -42.68 | -81.33 | -14.57 |

| - Evangelical | 3.93 | 4.39 | -7.83 | -3.10 |

| - Pentecostal | -11.97 | -11.97 | -18.28 | -6.13 |

| - Fundamentalist | -10.85 | -9.58 | -47.79 | -3.77 |

But the answer to their third hypothesis was the most surprising.

“Our third hypothesis was that geographical distance was going to be important somehow,” he says. “And no one had thought about this or looked at it, so we really didn’t know for sure how it was going to make a difference.”

Look at the contrast, he says, pushing the results table across his desk, between the national averages and the rates in adjacent counties — those that have a megachurch in the next county. There’s not much difference for mainline Protestants or Catholics, but the more conservative you go, the more damage you see.

| Affiliation | U.S. Average | Non-Adjacent Counties | Adjacent Counties | Core Counties |

| Mainline Protestant | -85.87 | -86.40 | -81.48 | -27.69 |

| Catholic | -19.73 | -19.82 | -20.49 | -3.96 |

| Conservative Protestant | -43.64 | -42.68 | -81.33 | -14.57 |

| - Evangelical | 3.93 | 4.39 | -7.83 | -3.10 |

| - Pentecostal | -11.97 | -11.97 | -18.28 | -6.13 |

| - Fundamentalist | -10.85 | -9.58 | -47.79 | -3.77 |

“You get down here,” he says, motioning to the bottom of the table, “and then all of the conservative Protestants are just getting slaughtered. It looks like they’re just being wiped out. And that’s different than any other measure we have for them.”

What’s more, he points out, evangelical churches are actually harder hit when there’s a megachurch in the next county than when there’s one in their own.

Wollschleger still isn’t sure what to make of this, but he says he believes that, because of our modern highway and communication infrastructures, the message from megachurches is getting out, and it’s drawing people from farther than ever before. He points to the example of that Atlanta megachurch, mentioned above, which draws congregants from seven different counties.

The problem for competing churches in these adjacent counties, he believes, is that they don’t even realize they’re in competition with the megachurch next door, so “there’s not the benefit of the sense of competition.” Meanwhile, competing churches in the same county have already girded their loins for battle.

Wollschleger admits that there are some limits to his results. The data is already a decade old, for example, and because they couldn’t really zoom in any closer than the county level, they couldn’t account for the vastly differing sizes of counties or measure real, as-the-crow-flies distances between churches.

His next step will be to add in the data from between 2000 and 2010 and look for changes. He says he’s also curious to see whether there’s a “tipping point” for megachurches, where “there can’t be more of them, because they exceed the carrying capacity of the ecology in which they’re located.”

But for the moment, he has his eyes on a new project: roller derby.

The proud father of two Lilac City Rollergirls, Wollschleger is training with the team to learn how the sport empowers girls and what qualities and characteristics make one team stronger, tougher and more successful than the next.

“I’m very excited,” he says.