In the first three miles of the climb up Cherry Creek Road, the rain turns to snow. The muddy road snakes through pine trees and the occasional house welcomes visitors with a “NO TRESPASSING” sign.

The snow gets deeper, and soon the road splits. To the right, a “Dead End” sign; to the left, a narrow road winds up to the top of the mountain, barely visible through the fog and impassible because of the season. It’s silent and empty. Depending on whom you ask, this is either the way this North Idaho mountain will always look, or the last winter it will be so quiet.

Here, a group of self-identified “patriots” says it plans to build an arms factory and a small-scale replica of its dream: a walled city safe from the collapse of modern society, home to thousands of residents who know their way around an AR-15. The Citadel, outlined extensively online, but led by organizers who refuse media interviews, would be a refuge from what survivalists often abbreviate as “when SHTF” (“shit hits the fan”) — the downfall and mass chaos they see as imminent, considering the politics and national finances of the day. This spot, the “Beachhead,” would be the administrative center of a new community, with the gun manufacturer, III Arms Company, as its economic engine.

But below this jagged mountain top is St. Maries, a sleepy logging town of 2,400, where locals say they doubt the project will ever happen, but still are fearful of being associated with it. On a fog-buried Thursday morning, more than one business owner and coffee-shop patron compares their fears for Benewah County to the history of Kootenai County, just 60 miles north.

“You’re a little worried because it’s a little out of the box, and you always worry a little about the anti-government types,” says Bryan Chase, who runs Timber Country, a sports apparel store his mother owns on Main Street. “I think back to when Coeur d’Alene had the Aryan Nations, and that gave all of North Idaho a bad name.”

Real estate agent Rick Powell, who owns Two Rivers Realty and leans back in his chair as he talks, says first that he doubts the Citadel will ever come to fruition. Then he too brings up Kootenai County.

“They’re going to come in here and imprint their character on this place,” he says, pausing. “But then again, that’s [because of] the media.”

The story has been getting plenty of attention. Salon, The Atlantic and New York Magazine wrote about the Citadel, and newspapers across the country picked up an Associated Press piece on it that came out last week. In January, it made the front page of the right-wing Drudge Report and was fodder for an episode of the parody news show The Colbert Report.

Those angling for the walled city aren’t necessarily St. Maries residents or even Idaho natives. The Citadel’s blog is peppered with people asking about the area, and the group’s website answers questions about the terrain and growing season. The people listed as managers of III Arms Company LLC and Citadel Land Development LLC are from the East Coast, according to documents registering the companies with the state of Idaho.

“We are confident [Benewah County] is an ideal fit offering low population density and, importantly, a shared world-view with most of its Liberty-minded residents: independence, self-sufficiency, and patriotism,” Citadel organizers write, though they maintain they can change their mind at their discretion. In a later update they add: “We have many amazing folks who are just waiting for the last pieces to fall into place to head to Idaho. Machinists, IT specialists, ex military, medical, education, farmers, a successful professional land developer — the list is awesome and growing daily.”

Citadel proponents aren’t professing white supremacism and say racism won’t be tolerated, but they join a list of other extremist elements who’ve put North Idaho on the national map. The infamous Ruby Ridge standoff between federal forces and Randy Weaver, a white separatist who had moved his family to North Idaho to escape the modern world, happened in the state’s northernmost county. In the mid-’90s, a settlement called “Almost Heaven” sprung up around Kamiah, another logging town 120 miles south of St. Maries, promising refuge from Y2k computer problems. Today, it’s all but gone.

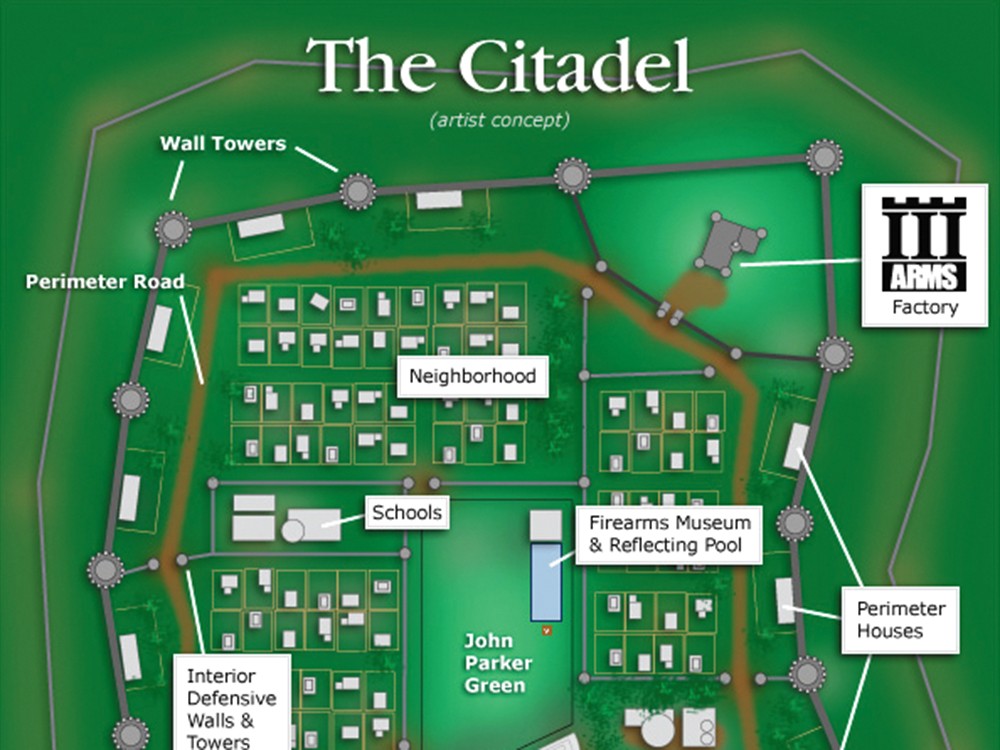

The specifications of the Citadel are blunt: two walls surrounding the complex, with more “interior defensive walls” inside. Within, there’s a firearms factory and a firearms museum, schools, houses and a farmers market. At the center is the “John Parker Green,” named for the militia leader who fought in the first battle of the Revolutionary War and told his men, “Stand your ground. Don’t fire unless fired upon, but if they mean to have a war, let it begin here.”

The “Patriot Agreement,” mandatory to be considered for the city (along with a $33 fee and a $208 deposit), lays out the requirements: Children will take marksmanship and gun safety classes, and once they’re 13 will begin annual tests on rifle and handgun target practice; every resident “of age” will keep an AR-15; every house must maintain a year’s worth of food, water and other essentials; everyone must be armed when visiting the “Citadel Town Center.”

Bailey Janda, a 22-year-old barista with bright blue eyes, works at a part espresso shop, part antique store in downtown St. Maries. She says a friend from California recently told her he heard about the Citadel and thought it sounded crazy.

“That’s right above my town,” she told him.

Still in its infancy, there’s no shortage of doubts about the project’s chances at success. The group only owns those 20 acres they say they plan to use as an administrative center, firearms factory and small-scale replica of the Citadel. They say it’ll take 2,000-3,000 to build the whole thing. The land they’ve purchased is rugged and not conducive to much development (it’s used now for hunting and outdoor recreation, says Powell, the real estate agent), and it’s unclear what funds they have for more.

Christian Kerodin, whose name is listed on the registration of Citadel Land Development LLC, was convicted in 2004 of felony extortion charges. The case alleged that he posed as a terrorism expert and offered security advice to shopping malls. Kerodin has argued he was fully qualified to offer such advice for money. In a video introducing III Arms Company, the Citadel’s gun manufacturer, a man identifying himself as the company’s president said Kerodin would have nothing to do with that aspect of the project.

In a county with nearly 11 percent unemployment, some have wondered how the 3,500-7,000 families organizers hope to accomodate will find jobs. The first wave will work at the firearms manufacturer, proponents say, and others will find the types of work that come along with any settlement — schools, stores, post offices.

Yet other unknowns are more nuanced. Despite being a conservative who can appreciate Citadel organizers’ personal property rights, Powell shakes his head at the probability of “getting 10,000 people to live together in the ‘me’ generation.”

“In my experience,” he says of today’s uncertain times, “people want privacy.”

In the county assessor’s office, quiet except for the drift of country music, a floor-to-ceiling rack holds transparent maps of land parcels in the area, labeled in pencil to track who owns them.

Karen Sindt thumbs through the maps, slips one out and lays it across the counter pointing out a small square marked “III Arms.”

“They don’t own 3,000 acres,” she says. “This is what they own.”

Sindt says she’s been getting calls from reporters all over the country about those 20 acres, and worries people are getting the wrong impression of her hometown.

“This is just somebody’s pipe dream,” she says. “We’re not a bunch of rednecks who want to build a walled city.”