Sitting at the foot of a hospital bed at Sacred Heart, the sky cold and black outside, Debi Hammel looked at her 16-year-old daughter and the machines and monitors that surrounded her.

Under a pink fleece blanket the family had brought from home, Lorissa’s bruises were starting to fade. Her swelling was going down, and the cut under her left eye was healing. Hammel had taped a photo from the homecoming dance to Lorissa’s IV pole and painted her fingernails and toenails bubblegum pink.

She didn’t look dead.

But Hammel knew without all these machines, Lorissa would be gone.

Hammel thought of all the things she wanted to say. She thought about who Lorissa had been and who she was now — her brain dead, the rest of her body in waiting. So many people would never know her. They would never see her smile.

With a blue pen, Hammel scribbled a note, but crumpled it up. Then another. When the words finally came, they were simple.

“My name is Debi,” she wrote, “and I want to tell you about my daughter and how lucky I feel about her helping so many people.”

Hammel knew her life wouldn’t be the same without Lorissa. A part of herself was dying in that hospital bed. But she couldn’t have imagined the journey she was about to take.

In death, Lorissa saved or improved the lives of at least 17 people — some through live organs, like the heart and lungs, others through tissue and bone — and in the four years since, Hammel has tried to track down those touched by her daughter. She’s also lobbied lawmakers to fix the intersection where Lorissa was killed, given speeches about her daughter’s impact and comforted people on both sides of organ donation.

To find the good in the bad, Hammel says, is the only way to heal.

“Love my daughter as I have and know she is in a peaceful place,” she wrote in that letter from Lorissa’s hospital room. “Dream for her, laugh for her, live.”

Lorissa was a 16-year-old fully immersed in being 16.

Pretty and popular, she loved shopping and driving. She was learning to snowboard with her older sister Lexie. Lorissa never went anywhere without her cellphone, which she used to take hundreds of photos, mostly of herself. She made sure her pale blue eyes were lined with dark eyeliner, her blonde hair was straight and smooth and her nails were painted — usually pink. Sometimes she wore a pair of hot-pink plastic glasses, even though she didn’t need a prescription. She called them “attitude glasses.”

She snuck out her bedroom window at night to meet up with boys and hid Victoria’s Secret lingerie in the back of her closet. When she was having a bad day, she’d sit on the floor in front of her mom and ask her to brush her hair while they watched American Idol.

In school, Lorissa did well, barely missing the straight-A goal her mom set, promising Lorissa $100 if she reached it. In the afternoons, she worked at the childcare center Hammel owns, spending time with special-needs kids.

She made snow angels with her younger brothers and sisters and borrowed her older sisters’ clothes without asking. She taught her brother all the moves to the “Soulja Boy Dance.”

“She loved life,” Hammel wrote in that first letter to the people receiving Lorissa’s organs, “and really was a very sassy, spunky, fun kid.”

Dave Blyton knows this stretch of Highway 195. He’s driven it every day for years. A short, round man with a soft voice, Blyton and his wife built a home in the ’70s on quiet acreage off the four-lane highway, just south of Spokane.

On a clear night in January 2009, Blyton was on his way home, returning with a new trailer he’d just bought. His daughter and her boyfriend were coming over for dinner, when the boyfriend was planning to propose.

The night was quiet and so was Blyton’s silver GMC pickup. He had his Bluetooth in his right ear, but no one on the line. There was nothing on the radio. He looked into the black night, eyeing the trailer in his mirrors and traffic ahead. At one intersection, a car pulled out in front of him turning right. He swerved into the left lane, narrowly missing a collision, and stayed there. That was close, he thought. As he approached the T-shaped intersection of the highway and Cheney-Spokane Road, Blyton saw a white Plymouth Breeze at the corner, waiting to turn left. As he got closer, the car didn’t budge.

Suddenly, the car jerked forward into the intersection, Lorissa’s profile lit up by Blyton’s headlights. She was looking straight ahead, he says. She never saw him.

Blyton slammed on his brakes, but it was too late. Lorissa’s car crumpled like a paper ball under the three-ton impact. Tangled together, the two spun into the median, the trailer careening south toward a snowbank.

“She’s dead,” Blyton thought. “I just killed a girl.”

As Blyton stepped out of his truck, dazed, there were people everywhere and a horn that wouldn’t stop.

His wife, Helen, would be close behind, and he was worried she would come upon the accident. He couldn’t find his Bluetooth. He couldn’t focus. Someone lent him a phone. Go home over the South Hill, he told his wife. Don’t take the highway.

A completely sober Blyton took a a sobriety test on the edge of the highway. It would clear his name, the officer told him. It would also set local media ablaze with rumors. People speculated about whether he was drinking, or that Lorissa had been using drugs or texting. But none of that would turn out to be true. Sometimes an accident is just that.

In a car stopped near the intersection, a stone-faced former cop and retired Marine, Dave McCann, told his wife to call 911 and then ran toward the wreck. Now a sales director for a medical equipment company, McCann thought there must be something he could do to help.

At first, the white car looked empty, but as McCann approached, he saw Lorissa’s thin body lying across the front seat. The doors were locked. McCann borrowed a crowbar to try to smash the side window out. No luck. He climbed through the shattered back window above the trunk and opened a side door.

Lorissa was breathing. She had a pulse. She wasn’t bleeding much, but she wasn’t responding either.

Another passerby was an off-duty EMT. The pair tried to stabilize her head in case she had any neck or spine injuries, but they didn’t have a collar small enough to fit her. So, McCann cupped his hands under the base of her skull, gently straightening her spine, and held her there.

“If you can hear me, just open your eyes,” he recalls saying. “Move your fingers.”

Five minutes passed, then 10.

“We’ve got help on the way,” he told her. “You’re going to be OK.”

Lorissa wasn’t OK.

She spent most of the night under operating-room lights. By 3 am, the monitors measuring pressure in her brain dropped to zero. At 7, a female doctor with a calm, gentle voice told Hammel her daughter was brain dead. I’m sorry, she told the family, there’s nothing I can do. Lorissa will never wake up.

“How do you know she can’t survive?” Hammel asked angrily. “Why is she still warm? Why doesn’t she look like she’s dying?”

Hammel cried, but she didn’t collapse the way the mothers do in movies. She just wondered: “Now what do we do?”

When a representative from LifeCenter Northwest — which oversees organ donation in the region — approached, Hammel didn’t have to think long. She remembered a brief chat she’d had with Lorissa and knew the answer.

Lorissa’s dad had been killed in an ATV accident in North Idaho just four months earlier. He was a donor, doctors told his daughters, and his cornea would help a child with vision problems see again. On the drive home from the hospital, her dad having just died, Lorissa told her mother she wanted to be a donor, too.

“I said, ‘That’s good to know,’ “ Hammel says, thinking little of it at the time. “I just kind of brushed it off.”

But when Lorissa got her driver’s license the next month, she went through with the decision and registered as a donor.

Hammel has a strong faith in God and in the idea that everything happens for a reason. It’s helped her cope with loss and with the fact that there is no one to blame for Lorissa’s death. So now, when she thinks back to that moment, she believes that’s part of the reason Lorissa’s dad died before she did.

“I think he led that path for her,” she says.

Most of Lorissa’s vital organs had been crushed by the accident. Her spleen and colon were ruptured, her left lung collapsed. Brain death worsened her condition, cutting off her body’s ability to regulate blood and oxygen flow to her organs and leaving her condition unstable. So LifeCenter’s medical personnel were left with a choice: Take the organs they could see were OK now — the pancreas and one kidney — or ramp up efforts to heal her other organs, a young heart, liver and set of lungs.

Angela Brooks remembers Lorissa’s doctor’s advice: “Get what you can before you lose everything.” But nurses like Brooks look at things differently than doctors for the living do. They’re able to use medicines that would shock a body with a living brain, but can help restore organs in the brain dead.

The process takes time, though, and that can take a toll on families. Every day Lorissa’s body lay hooked up to machines and monitors was another day her family couldn’t quite say good-bye.

“It was just taking so long,” says Jason Hammel, Lorissa’s stepdad.

Some families change their minds because the waiting is too hard, Brooks says. Lorissa’s older sister Kayla resisted becoming an organ donor for the first year after Lorissa’s death because she worried about her family going through that wait again, Hammel says.

As days passed, doctors worked to try to strengthen Lorissa’s lungs, at first just to get better oxygen flow to the rest of her organs, but ultimately to prepare for donation. By the time they took her to the operating room, they had recipients around the country waiting for her heart, liver, pancreas and both lungs.

As nurses rolled Lorissa’s bed toward the OR, the weight of the final good-bye hit Hammel like a sucker punch.

She collapsed. Her husband and a male nurse she calls “Big John” carried her from Lorissa’s bedside, her sobs echoing through the empty hallway as a pair of metal doors slammed behind her.

“You have to let go,” nurses told her.

Inside the OR, teams of surgeons stood around Lorissa’s open chest, surveying what they’d come for. The liver team takes the longest to prepare for removal, but the heart is taken first because it lasts the shortest amount of time outside the body. The lungs came second, then the liver and pancreas. Later, another team took her tissues, corneas and a part of her shoulder blade, a special donation for a boy who’d been crushed in an accident. Lorissa’s kidneys were unsalvageable.

In a series of tests at Spokane’s Inland Northwest Blood Center, lab technicians determined which recipients would best accept Lorissa’s organs. Then LifeCenter coordinators called surgeons around the region, looking for those who would accept her organs for their patients.

“The biggest thing I’m grateful for is that Debi gave us the time to turn her around. … She was so clear from the beginning to save lives of others because she knew Lorissa’s life could not be saved. That, to me, is heroic,” says Brooks, who this year presented Lorissa’s story to a national conference as a case study about the progress that can be made even on severely damaged organs.

Organ damage is a common problem and part of why few deaths actually result in donation. But new research is testing ways to help damaged organs heal without having to keep a person’s body alive. A recent major advance places donor lungs in a plastic dome attached to a ventilator, pump and filters. There, kept at normal body temperature and conditions for three to four hours, the lungs can begin to heal with the hopes they’ll become suitable for transplantation.

Progress comes from a change in philosophy, too, Brooks says. When she first started this work nine years ago, it wasn’t uncommon to rule an organ out with first tests. An imperfect cardiac echo? The heart must be no good.

Now, because of success stories like Lorissa’s, “we don’t just walk in, look at a patient and start ruling things out,” she says. Now, everything has potential.

“Knowing 18 people die every day waiting for a transplant,” Brooks says, “I can’t in good conscience rush a patient to the OR knowing I could fix one more organ and save one more life.”

“I understand after talking with LifeCenter that families feel guilty because of my loss,” Hammel wrote from Lorissa’s bedside. “Please don’t feel guilty, my daughter chose to save you and as much as I miss her I am OK with knowing that someday I may be able to meet you and share in your joy.”

Months passed, and no one responded.

Hammel planned Lorissa’s funeral like a wedding because she knew she’d never see her daughter get married. She made sure Lorissa was cremated in her favorite $100 jeans and flip-flops. She looked up Lorissa’s cellphone records to see if she was talking or texting when she crossed the intersection. She called witnesses and tried to find the EMTs who responded.

A few weeks after the accident, she met Dave Blyton, the man who hit Lorissa, for the first time at a community meeting about how to improve the intersection — one of the county’s most dangerous. Blyton and Hammel soon started to help each other heal. He suffered his own trauma and guilt from Lorissa’s death, and Hammel wanted him to know she didn’t blame him. Since the accident, they’ve built a friendship, even spending Christmas together.

Hammel, meanwhile, fought with her husband and drifted from her other children. Between their dad’s death and Lorissa’s, Hammel’s oldest daughters had trouble coping. Lexie, then a high school senior, skipped school and slept all day for months. She resented how much time Hammel spent trying to find the people involved in the accident and the ones who’d received Lorissa’s organs. She just wanted Hammel to move on.

During the days, Hammel wandered. She couldn’t return to work, where she’d last seen Lorissa. One day she bought a $1,200 toy Yorkie at a mall pet store; Lorissa had always wanted a dog she could carry around in her purse.

“You have to learn to kind of relive life,” Hammel says now.

Hammel still couldn’t get her mind off the people who’d gotten Lorissa’s organs. Were they grateful? Were they taking care of themselves?

She sent another letter.

“I am writing in hopes that you’ll let me know how you are doing,” she typed. “All the organ, tissue and sight centers have told me that many people don’t know how to respond to a donor family. I want you to know that I have no expectations. I am wishing you only the best and am thankful that Lorissa was able to hopefully enhance your life quality.”

She told them she is “a mom who tries to make the best of every situation,” and that she was pushing for changes at the intersection and thinking of starting a support group for people who’ve lost a loved one.

“I believe everything happens for a reason,” she wrote. “With that being said I do believe you are supposed to have a part of Lorissa. … I hope to hear from you someday in the hopes she has enhanced your life. Breathe for her, dance with energy, sing and see life as she would.”

“I can’t begin to express in words my gratitude,” were the first words Hammel heard back, scrawled in black ink on a piece of jagged notebook paper.

Jolene Evans is a short, plump 59-year-old woman who’s not afraid to talk about her lengthy list of health issues, her bitterness at losing her job because of them, or the feelings she had during her nine months on the transplant waiting list.

“You go through guilt because you know somebody has to die for you to get a lung transplant,” she says. “But then as you get worse — this is awful — as you’re going down and you see traffic accidents on the TV and you’re [thinking] ‘Oh, are they available?’”

Evans faced her first serious health issues in 2004, when doctors began to worry that what had previously been diagnosed as asthma was something far more serious. She went on and off oxygen tanks over the next few years, feeling her condition deteriorate and then get better, only to slip again. By 2008 she was using more than 20 liters of oxygen a day for a life of minimal physical exertion — she’d spend most of her time knitting or going on drives just to get out of the house. Her lungs weren’t holding as much air as they should have and weren’t properly distributing the oxygen throughout her body.

As winter approached, she was carrying two-foot-tall metal tanks with her wherever she went. Her legs ached, and she’d be short of breath after a middle-of-the-night trip to the bathroom. Doctors believed she would die within a year.

Nearby, Evans’ two sons were building their adult lives — jobs, fiancées, plans for children. Her nieces and nephews were growing up too. She worried she’d miss graduations, weddings and births of grandchildren.

Even when hospital staff called her to tell her they’d found a set of lungs — Lorissa’s — Evans was skeptical. They’d warned her the bad car accident her donor had suffered meant the lungs might not work, and a winter storm might mean trouble for the surgeons on their way to Spokane.

“It’s not going to happen,” Evans thought as she waited. “It’s fine. I’m fine.”

Six hours of surgery and two Oxycodone-hazed days later, Evans awoke to new lungs, but not the new start she’d imagined. Her first breath was good, but it wasn’t the deep relief she was expecting. Doctors told her the new lungs didn’t fit quite right in her small chest cavity. Her diaphragm was too high to allow them to work at full capacity.

“I thought I got shortchanged,” Evans says. “I was frustrated and angry because I couldn’t do what I wanted to do.”

She spent four more months on oxygen. But slowly, as she started to accept the lungs, they began to breathe better. By the fall she didn’t need oxygen tanks. She took road trips around Washington and Oregon to see waterfalls and beaches.

Evans got her first letter from Hammel in April 2009 — her case worker at the hospital wanted to give her time to recover from the January surgery and complications that followed. She hung Lorissa’s picture in her kitchen and talked to it every day, but she didn’t know what to write back. Five months later, she wrote the only things she could think of. She was sorry for the family’s loss and grateful for their gift. She would never forget it. She’d even like to meet them.

“In July I went on vacation with two of my sisters and their husbands,” she wrote. “We went to the beach and I saw a T-shirt there that reminded me of Lorissa. It said ‘live, love, and laugh.’ I remembered a sentence you had written earlier about living for her, laughing for her and dream for her. I thought this was appropriate.

“I am taking care of myself and striving to live a meaningful life. Thank you again.”

Soon after Hammel opened Evans’ letter, she got another response. A woman called her at work. She said Hammel should be sitting down.

“I know this isn’t the way to do this,” the voice said, “but in my heart I need to tell you who I am.”

Hammel was confused, but she listened, gazing at the sunny day outside.

The woman on the line said her 21-year-old son needed a cornea transplant after he started losing vision in his left eye. It was Lorissa’s cornea he received.

The emotions overwhelmed Hammel. The communication process is usually regulated by LifeCenter, allowing introductory letters back and forth first before any identifying information, let alone an unexpected phone call. But the woman had Googled Lorissa’s name in Spokane and read the media coverage. She saw Hammel’s name and that she owned the daycare.

“This is not how it’s supposed to go,” Hammel thought.

Crying, the two mothers ended up talking for more than an hour. They told stories about their own kids, but were really more interested in the other’s.

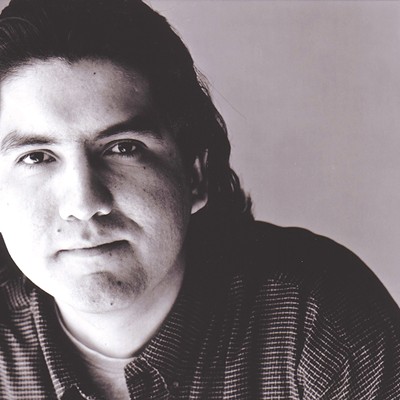

Hamid Wahid is an athletic junior at Evergreen State College with a toothy smile and a habit of rarely being on time.

His parents immigrated from the small South American country of Guyana. His grandparents, aunt and uncle all live in the same neighborhood in Lacey, a sleepy green suburb of Olympia, where he lives with his mom and stepdad.

On Jan. 1, 2009, Wahid woke up with a sore left eye. He had spent New Year’s Eve drinking with a small group of friends — one of them was home on leave from the Army and was leaving the next day. He thought he must be hungover as he made his way home, squinting into the bright day, his head pounding.

But as evening approached, the soreness in his eye was getting worse, and his vision was starting to blur. He couldn’t make out things even a few feet away. It took only a few minutes at a clinic in Olympia for doctors to tell him his cornea was damaged, and he’d need to see a specialist. There, he learned he’d need a transplant and went home with an eyepatch. Underneath, the eye watered and ached, bulging outward into a cone shape.

As weeks passed, he worried about the uncertainty of waiting for a transplant. If he never got a donor, he might never play basketball or drive again. He wouldn’t enjoy running outside in the same way. A new acquaintance told him she’d seen him walking in town the other day. She remembered him because of the patch. It wasn’t about life or death, but normality.

“I’m only 21 and I might have to wear an eyepatch for the rest of my life,” he thought. “People are going to think I’m a freak.”

But on a cold, gray Monday — as Lorissa’s brothers and sisters dressed in their best clothes for her funeral — Wahid watched surgeons sew sutures around his new cornea. Cornea transplant recipients receive pain medication and a sedative, but can remain awake throughout the procedure. With “awful music like Michael Bolton” in the air, Wahid stared forward at the clock as the surgery progressed. Doctors cut off the faulty cornea — a thin transparent piece that covers the front of each eye and helps it focus — and sewed in a new one.

“It looked like how you would stitch cloth,” Wahid says.

Slowly, the pain from the surgery faded, and his vision came back. He watched the Super Bowl and saw Mall Cop from the back row of the theater. He started going to class again, getting rides to meetings for group projects, and nearly a year later felt the last stitches loosening in the corner of his eye, ready to come out.

He wondered whose cornea he’d been given, but assumed it would be impossible to ever know. He figured it was probably an older person, someone who’d died of natural causes, but never asked.

“To me it was like receiving a gift from an anonymous person, like Santa had wrapped up this and gave it to me without a name,” he says. “I started feeling guilty because not only did I have this cornea, but I didn’t know who to thank or whom to appreciate.”

When his mom told him she’d found the mother of his donor, that she’d called her at work and that they were going to meet within the week, his head spun. He’d finally get to thank the mother of the person who saved his eye, but that meant facing the fact that Lorissa’s life was cut short at 16.

“She was just beginning her life,” Wahid says. “I’m 25 and I feel like I’m just beginning my life. Here’s this little, sweet, young girl.”

In a sports bar, he and Hammel talked for hours without ever ordering food. Hammel looked into his eyes and saw nothing of Lorissa. She’d expected them to look familiar. But, she reminded herself, the cornea is just the outer lens. It doesn’t change the way the eye looks.

As she listened to Wahid tell her about himself, she started to see Lorissa. He’s energetic and friendly, feeding off others’ attention.

“He is so my daughter,” Hammel says.

Later that night, over red velvet cheesecake in a Bellevue Cheesecake Factory, Hammel found herself feeling something very different: disappointment. There, she had arranged to meet Evans, Lorissa’s lung recipient. She looked older than Hammel had expected. Old and tired.

“I thought she should be younger — Lorissa was young — somebody who would have all these years left in life,” Hammel says.

As Hammel got to know Evans better, in the restaurant and other visits in the months and years to come, those feelings began to soften. The transplant brought Evans closer to some of her family and bought her more time with her sons. She’s since seen one of them become a father and the other get engaged. Hammel knows Lorissa would have been happy to give that opportunity to someone like Evans, no matter her age.

At those first meetings, Hammel told stories about Lorissa, the things she loved and why she became a donor. She sent Wahid and Evans home with photo albums: Lorissa snowboarding in a pink headband; smiling in her black-and-white, floor-length homecoming dress; and flashing a peace sign at the garbage-eating goat in Riverfront Park.

Evans keeps the album handy. She asks Lorissa how she’s doing and thanks her for her gift. Wahid keeps his on a shelf, but says it’s hard to look at. It reminds him of the family’s pain.

“I really think of the family. When my eye is irritating, I think of how the mom is feeling losing a daughter,” he says. “When I see [Hammel’s] Facebook post of something happy, I’m happy as well. I’m happy to see her smiling because I just can’t imagine what she has to go through on a daily basis.”

Hammel knows Lorissa’s pancreas was transplanted into a 61-year-old Minnesota man, but that it didn’t function. She knows Lorissa’s other cornea went to a woman in her 70s who never wrote back. And she knows about Mandie, the 21-year-old Seattle woman whose skin and eyes yellowed more every day she waited for a liver transplant. Within 24 hours of receiving Lorissa’s liver, Mandie started to feel and look normal again, she told Hammel in the first letter she sent.

On small cream-colored stationery, Mandie shares condolences and gratitude. She says she loves hair, makeup and shopping, and that she has a picture of Lorissa framed in her room. She includes a Bible verse about finding love in times of grief.

“Lorissa is like a hero to me, she saved my life!” Mandie writes near the end of her letter. “I promise to never forget her and I will take care of what she has given me.”

Hammel still hopes to meet Mandie someday. She heard from LifeCenter that she’s moved out on her own, and it reminded her of watching her own daughters experience those milestones.

From the beginning, Hammel has wondered specifically about one recipient: the person who would feel Lorissa’s heartbeat. She wrote in that first letter that she looked forward to meeting the person someday — “to listen to her heart and have you see me or know you have been able to live on, maybe see how you look at life now.”

Hammel learned that Lorissa’s heart was transplanted into an 18-year-old California woman who liked to sing and dance, though the recipient never wrote. In December 2009, as the one-year anniversary of Lorissa’s death approached, Hammel sent the woman a small Christmas tree ornament — an angel holding a heart in her outstretched hands.

But in January, LifeCenter told her the young woman had died. They waited until after the holidays, they told her, because they didn’t want more sorrow to dominate the family’s first Christmas without Lorissa. Hammel grieved for a woman she’d never known.

“It was kind of like losing Lorissa all over again for that day,” she says. “You feel responsible and you wonder — you just wonder.” She wondered if the family blamed her or regretted taking Lorissa’s heart.

But, she adds, “that family had 10 months with their daughter — 10 months I would kill to have.”

As Lorissa’s accident faded from the headlines, Hammel was trying to figure out how many vans she’d need to rent to get her friends and family to Olympia.

She was scheduling meetings with lawmakers who would decide whether the intersection deserved new money, and scribbling down the things she wanted them to know. And just 56 days after she saw Lorissa’s pink cheeks for the last time, she sat before the Washington House Transportation Committee with a group of supporters behind her.

She fought back tears to tell legislators why they should support a bill funding first an exit and eventually an overpass at the intersection. She told them how she and Lorissa had practiced driving through that intersection, and how since the accident she had trouble going to the daycare where she’d last seen Lorissa smiling. Blyton spoke too, as did Thomas Grieb, a man who was paralyzed in a collision at the same intersection. There had been 80 accidents there in the past decade, they told lawmakers. It was time to do something.

“If after hearing this your mind is still not made up, look at the people sitting behind me,” Hammel said, her voice cracking. “Look at my children, who have more understanding than they should about death and how easy things change.

“In the end, be a part of making something good come out of something so bad.”

It was the first in a long string of times Hammel would tell Lorissa’s story in hopes of effecting some change and keeping her memory alive. Hammel speaks to other parents who’ve lost children and to groups on all sides of the organ donation process, from nurses to other donor families to recipients. As progress continues on the intersection — an overpass is the works — she rarely turns down a TV interview, often on site near an “In memory of Lorissa Green” sign.

Alongside lawmakers and construction workers at a groundbreaking on the overpass earlier this month, she smiled as she watched dirt fly off the front of her gold shovel.

On a sunny Wednesday morning, Hammel keys up a PowerPoint presentation as teenage chatter fills a small auditorium at Cheney High School. Freshmen, just a year younger than Lorissa when she went there, file in looking for seats near their friends.

In jeans and white Nikes, Hammel grips a microphone and looks into the sea of faces. She says she’s there to talk about organ donation — not to convince them to become donors, but to at least start thinking about it.

“No one in this room is invincible,” she says.

She asks them to go home tonight and tell their parents what they want if something happens to them.

“What do you mean, like, when something happens to you?” one girl in the audience asks. “Like if you die or something?”

Hammel tells them about her daughter’s accident and the four hellish days she spent in the hospital.

“I’m not going to lie to you, this is the worst thing I’ve ever done,” she says bluntly. “Losing a daughter makes you not want to get out of bed some days. But … I’m not the type of person that would just not get out of bed, so I focus on the positive things and where we’ve gone with this.”

The two-second conversation Hammel and Lorissa had about organ donation after Lorissa’s dad died made things easier, even amidst the pain, she tells them. That’s why the few seconds you’ll spend with your parents tonight are so important.

“They will never think about it again,” she says, “unless something happens to you.”

Hammel’s given this talk more times than she can remember. She used to cry, but now some of the emotional sting is gone.

By the end, the kids will be anxious and chatty. But for a few moments, as she flashes through images of Lorissa as a smiling 16-year-old, with life ahead of her, the room is quiet.

THE HISTORY OF DONATION

Early 1900s: As blood-typing technology emerges, doctors in France start experimenting with organ and tissue transplants. In 1905, a laborer blinded in an accident while working with lime receives the first cornea transplant in what is now the Czech Republic.

Dec. 23, 1954: The first successful living organ transplant is performed in Boston, where doctors transplant a kidney from Ronald Herrick to his identical twin, Richard, who lived another eight years until his original disease destroyed the new kidney.

1967: The first successful heart transplant is performed in Cape Town, South Africa.

1983: The FDA approves Cyclosporine, the most successful anti-rejection medicine to date, helping transplant recipients live longer.

1984: In a major medical milestone, two thirds of all heart transplant patients survive for five years or more. That year also marks the development of the United Network for Organ Sharing database, which doctors use to prioritize those waiting for transplants.

2010: The first full face transplant is performed in Spain for a man injured in a shooting accident.

MYTHS AND STIGMAS

Organ donation enrollment is on a steady climb, with a 7 percent national increase from 2010 to 2011. But more than half of Americans are still not registered organ donors. Pro-donation agencies blame that on common questions and misconceptions.

Some people fear they’re not healthy enough to donate, but very few medical conditions actually disqualify someone from donation completely. Some wonder about religious beliefs. While not every religion’s view is clear, all major faiths in America approve of donation.

Others worry doctors won’t do as much to save them if they’re a known organ donor or wonder whether people can come back from brain death. In fact, the doctors who try to save injured patients are not the same ones who could later prepare their organs for donation. A patient’s doctors are required to do everything they can to save the patient’s life and don’t know the patient’s donor status.

Some families worry donation may add to their medical costs or prevent them from having an open-casket funeral. Donor families bear no costs for donation, and organ recovery surgery does not prevent an open casket.

WHO GOES FIRST?

Today, there are more than 117,000 people waiting for lifesaving transplants — a new name is added every 10 minutes — but many of them will never get the help they need. On average, 18 people die every day waiting for a transplant.

That’s because a huge majority of people who die never become organ donors. Even those who register to donate often die of causes or accidents that make their organs unacceptable for transplant. Of the 2.5 million people who die every year in America, only about 8,000 become organ donors, according to LifeCenter.

So those waiting for transplants are registered in a national database to prioritize who will get the very few organs that will become available. The United Network for Organ Sharing connects doctors whose patients need transplants with organ procurement agencies, which work with donors and their families.

Patients are prioritized based on time spent on the list and level of sickness. Once a donor dies (or a living donor is approved for donation), doctors and lab technicians test donor and recipient blood type and antibodies — which our bodies create to fight off foreign objects or infections — to determine which recipients will accept which organs. Those factors narrow down the hierarchy of recipients for each donor: Who’s the sickest person whose body will accept this organ, and is he or she close enough for a team of doctors to retrieve the organ and transplant it in a reasonable time?

Doctors for those at the top of the waiting list can accept or reject the available organ, based on how well they think their patient will accept it. It’s a process that never gets easier, says Dr. Timothy Icenogle, who oversees Sacred Heart’s heart transplant program.

“The judgment call comes down to did you make the right judgment call or didn’t you?” Icenogle says. “If you didn’t, well then the patient’s life is on the line and that hangs on your shoulders.”

HOW TO REGISTER

While registration isn’t the only way to end up an organ donor — families can give consent — it’s the most likely. Uncertainty and the shock of an unexpected death can cause families who don’t know their loved one’s wishes to shy away from donation.

If you want to be a donor, say “yes” the next time you’re asked at the DMV or use these methods:

In Washington: Go to donatelife.net (here, you can even specify which organs you want to donate) or mail a letter with your name and address to: Donate Life Today Registry, 11245 SE 6th St., Ste. 100, Bellevue, WA 98004

In Idaho: Visit yesidaho.org. You can register on the site or download an application and mail it to: The Idaho Donor Registry, 230 South 500 East #290, Salt Lake City, UT 84102. Or call: (866) 937-8824