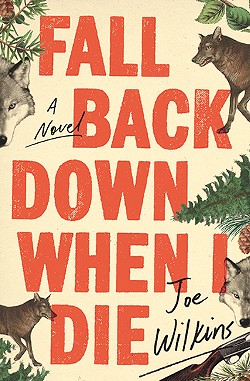

Fall Back Down When I Die is a story of realistic, complex characters whose lives intersect on a big canvas, as big as Eastern Montana. Joe Wilkins grew up there and infuses his novel with a sense of personal attachment to both the history and current realities of life and conflict across the vast landscape.

For Wilkins, reading at Auntie's on Saturday, Western open spaces are both real and metaphoric. "There were some distances you could not cross," he writes, later describing the land as a place where "failures of the nation, the failures of myth, met the failures of men." With that, Wilkins captures the overarching context of his story. But the strength of this book — and it is powerful — is in smaller, intimate moments as the story unfolds.

Wendell, the protagonist, grew up in a small town in the Bull Mountains. He was a star athlete in high school until an injury put an end to that, just another defeat in a short life. When we meet him, his father has disappeared, his mother has taken her own life, he is living alone in a trailer and working as a farmhand for a neighbor. His solitary life changes suddenly when a scrawny 7-year old boy, son of a cousin, is delivered to him by a social worker from Billings. The boy's name is Rowdy.

The reader soon knows Wendell as a gentle soul. We see him respond with tenderness to the surprise of his new responsibility, accepting the reality that the boy doesn't speak and feeding him saltines smeared with margarine, as many as he wants. All the while Wendell keeps up the patter of one-sided conversation with the child.

While that sweet relationship develops, the story builds around the conflict of overuse of public lands, the historic, seemingly endless conflict in the West, from the Sagebrush Rebellion, to the so-called Wise Use Movement. The conflict is fueled by a deeply rooted resentment that many longtime residents hold for state and federal government agents charged with enforcing rules over the land and the critters who inhabit it. The resentment occasionally leads to violence, and so it does in Wilkins' fictional version where the wolf is the catalyst.

As the plot develops and the characters — Gillian, a school teacher, and Maddy, her daughter — are more fully developed, the book becomes a page-turner. Advice to readers: Resist the temptation. Wilkins, who has written poetry and a well-received memoir, has a way with the language that deserves the reader's notice. Linger over sentences and phrases that evoke the full range of the senses — sounds, colors, touch and taste. A night sky is "star-scatter," dogs are "brown, mottled, rib-skinny," grasshoppers "flung themselves through the dry grass." Rowdy, asleep on the bench of the truck, "stretched his thin legs out until one of his socked feet just touched Wendell's leg."

The story moves to its dramatic end in small moments and finely crafted sentences. The reader knows both place and time as Wilkins drops in cultural clues — Avett Brothers fans, binge-watching The Wire, Obama and George Bush references.

This is ultimately a story about the consequences of grievance and entitlement as Western myth confronts the complicated reality of the modern West and its more recent settlers. The story has a familiar antecedent in the Bundy episodes in Oregon and Nevada. And for those of us who live in or near the open spaces of the West and experience the inevitable culture clash in our daily lives, Fall Back Down When I Die has resonance beyond the beauty of the language and appreciation for a well-told story.♦

Joe Wilkins: Fall Back Down When I Die reading • Sat, April 13 at 7 pm • Free • Auntie's Bookstore • 402 W. Main • auntiesbooks.com • 838-0206 • Also appearing at Get Lit! 2019