For a moment, it seemed like Spencer had run out of chances. He had already been expelled from one high school by the time he was a sophomore in spring 2015. Then, at Spokane's North Central High, he lit a teacher's door poster on fire, leaving it to burn as he walked away.

That school, too, told him to leave and never come back.

He's since been in and out of juvenile detention, treated for the psychotic episodes that got him kicked out of school, and placed on electronic home monitoring and probation.

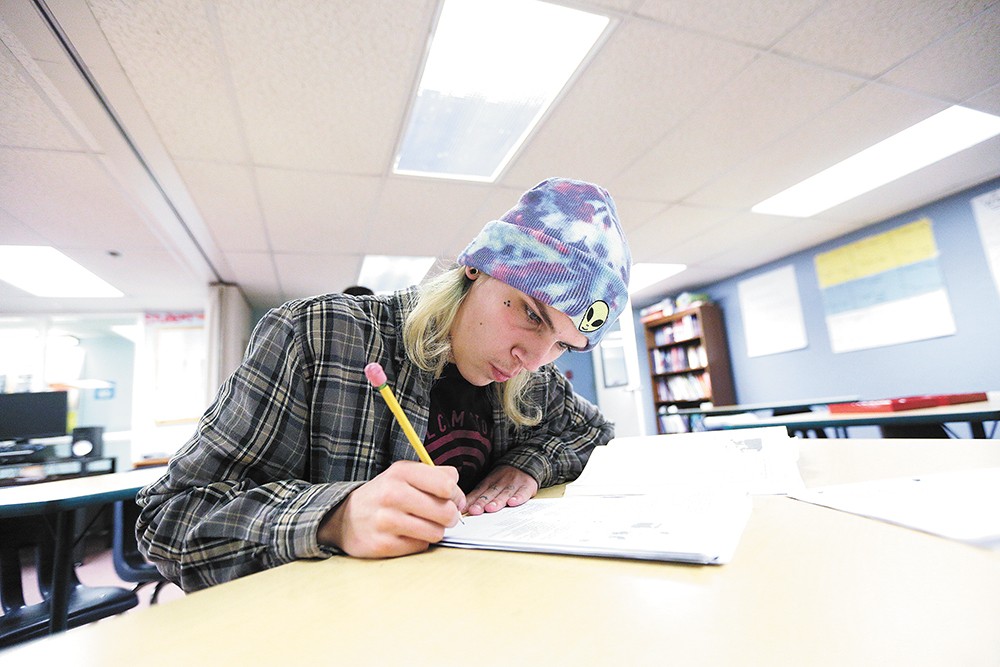

But on a frigid December day, the 16-year-old is hopeful.

"Tomorrow will be my last day of high school," Spencer says.

That's because Spencer's education continued even though he never went back to a traditional high school. He had no choice but to do schoolwork while he was in juvenile detention. When he got out, he was court-ordered to continue learning at Structured Alternative Confinement (SAC), a school adjacent to the juvenile detention facility for kids who commit crimes.

There, Spencer flourished. Now, he's ready to finish secondary education on his own terms and earn his GED.

"I just really like the atmosphere here," he says. "I came in with good intentions, and I'm leaving with my GED, which I never thought I was going to be able to do."

Thousands of kids in the state attend schools in an institution like the juvenile detention facility each year. In 2014-15, there were nearly 11,000 institutional education students in Washington; in Spokane, there were more than 1,000.

These schools, often forgotten in the public school system, can represent the last chance for a good education among the most vulnerable kids — those with learning disabilities, behavioral problems, mental health issues or drug addiction. But right now, these schools say they are hampered by a lack of resources. The state's funding system for institutional education, which hasn't been updated in 20 years, leaves these schools scraping by to pay for teachers, counseling services and materials.

As the state legislature has increased its general education funding for public schools as part of the state supreme court's McCleary decision, a new report released by the Washington Office of the Superintendent of Public Instruction calls the education for kids in institutional programs "neither fair nor equitable."

Since 2010-11, total state funding for institutional education in Washington has dropped by nearly $3.5 million, according to OSPI data. And while that largely is because the number of students has dropped due to changing juvenile justice laws, that doesn't mean institutional programs don't need that money, says Kathleen Sande, institutional education program supervisor for OSPI.

"Even though the number of kids has lowered across the state," Sande says, "the toughness and the rigor we need to use for those kids is higher. We're needing more psychologists, counselors and paraeducators in the classrooms."

The OSPI report calls on the state legislature to adjust its outdated way of funding institutional education.

"These kids are going to be everybody's neighbors," says Sande. "They're going to move in right next door again, where they were, when they get out. And the public needs to think about: Do they want them to come out without an education? Or do they want them to come out with a better education?"

When kids are sent to the Spokane County Juvenile Detention Center, they spend hours a day in school. The coursework is supposed to be tailored to each student's individual needs and coordinate with what they were learning before they were placed there.

That means teachers like Dan Fuller may have a classroom full of a half-dozen kids who are all different grade levels, and all learning something different. The average length of stay at the detention center is about 12 days.

"It's not a whole lot of time, but at least it's a springboard to get them started," Fuller says.

The goal is to prepare students to find a way to get back to school, wherever that may be, says Larry Gardner, principal of the detention school and SAC school. Gardner also heads the Martin Hall Detention Center school in Medical Lake, which serves kids from nine Eastern Washington counties other than Spokane.

When kids get out of juvenile detention, many end up with a court order to attend the SAC school next door. Both schools offer smaller class sizes and more individualized education, and Kathi Tribby-Moore, a teacher at the SAC school, says that's just what they need.

"These kids are kids a lot of society has given up on," she says.

The number of kids served in institutional schools has gone down in recent years, in part because of the Juvenile Detention Alternatives Initiative, aimed at reducing overcrowding in detention centers. But the ones who still fall into juvenile detention, says Tribby-Moore, often are the most at risk, even though the schools get less funding if there are fewer students.

"As the needs of our kids have increased," Tribby-Moore says, "our funding has decreased."

Mick Miller, assistant superintendent for the NorthEast Washington Educational Service District 101, oversees the three programs in the area. He says the programs have had to "tighten their belts" because of the lack of money coming from the state. For example, while many of these kids need mental health services, Miller says the only way they can provide a mental health counselor is from a grant, not state funding.

"We're at a point where we're running about as efficiently as we possibly can," he says.

One of the main problems with the state's funding formula is how the state decides how to allocate money each month, based on the count on the first day of school, Gardner says. The count days happen on the first day of the month that school is in place, but Gardner says that doesn't make sense, because there could be an influx of kids who come in to juvenile detention the next day. He argues that it should count the average of the month, not the one-day count, like in other public schools.

The report recently released by OSPI agrees. And in addition to the change in the funding formula, the report recommends an additional $12.9 million for 2017-18 for institutional education across the state.

That would allow Gardner to hire more staff, such as certificated math teachers, along with another educational advocate to help kids transition out of the institutional schools. Since they currently don't receive extra funding for special education students, more money would also help hire a mental health counselor.

"Are we on our last legs? Absolutely not," Miller says. "Could we do more with greater resources? Yes, we could."

Similar to detention facilities, students stay overnight at rehab facilities like Daybreak Youth Services. There, too, they can continue their education.

But Daybreak and other area youth rehab centers, like Excelsior and the Healing Lodge, are not considered to be institutional education schools.

"Although we should be," says Annette Klinefelter, executive director for Daybreak.

Instead, Daybreak gets money from Spokane Public Schools. Even though the district recently increased its allocation for Daybreak, Klinefelter says it's still not enough.

Klinefelter says it would be a "huge game-changer" if youth rehab centers instead received money directly from the state.

"It would be a much more appropriate fit, because we are nothing like a public school. We are much more like an institutional education school," she says. "So being under that category would make so much more sense."

The Daybreak facility served more than 200 girls last year, says Sandy Tipton, Daybreak's only teacher in Spokane. Excelsior served about 140, and the Healing Lodge served 165.

Tipton says that teens can be in treatment for months at a time — much longer than the average stay at a detention facility. Like the juvenile detention school, Daybreak bases its curriculum on what students were working on in their previous school. Rehab centers also have a large population of students who are referred there from a juvenile court.

Klinefelter says that more teachers are needed to improve the teacher-to-student ratio at Daybreak, which she says is now at one teacher for every 30 kids.

"Sandy does a phenomenal job," Klinefelter says. "I just can only imagine what she could do if she had two additional teachers to support her."

Spencer, long blond hair flowing from beneath his beanie, remembers a teacher he had in third grade at Longfellow Elementary School. He remembers her because she actually talked to him, unlike other teachers who saw him as just another student from any other class.

If he would get in trouble, he would go out in the hall and she'd give him a dictionary. It made him like school.

"She really just understood and set me down the right path," Spencer says.

He says he didn't have any other teachers like that until he came to the SAC school, where the three teachers can spend more time with students. But when he tells people about the school, they usually have no idea what he's talking about.

Elisa Vanhoff, one of Spencer's teachers at the SAC school, says the staff understands that the kids they serve all have experienced some kind of trauma in their life. If students act out, they work with them, kind of like Spencer's third-grade teacher.

That means kicking a student out of school is not really an option, Vanhoff says.

"Where else would they go?" ♦