She hoped it was just a sprain — nothing that some ice and a little rest couldn't fix. "Someone said, 'I thought I heard a pop!' and I couldn't feel my ankle. It was all tingly," Jenna Carroll recalls from her dining room table, a stack of medical bills in front of her.

Not knowing the true extent of her injury — a fibula fracture near her right ankle — Carroll still drove herself home that night after team practice with the Inland EmPower Derby league.

"I didn't want to go to the emergency room because it's too expensive. So I went home, and my husband carried me up the stairs to our apartment," she recalls. "At 3 am, I got up and crawled to the couch and texted my brother: 'I need you to take me to urgent care.'"

Now, two years, one surgery, seven bone screws and more than $6,000 in medical bills later, Carroll's ankle is back in working order.

Her story is not unique, nor is it one of the worst-case scenarios of how an unexpected need for care, combined with increasingly high health insurance deductibles, can create a serious financial setback.

The multistage rollout of the Affordable Care Act's insurance marketplace and resulting decline of the uninsured population has in part overshadowed a troubling trend in health care: the large number of Americans who are considered underinsured. These are many people like Carroll, who are enrolled in health insurance plans that ultimately shift a large burden of costs back to their policyholders.

A 2014 biennial study led by Commonwealth Fund, a nonprofit health care policy advocate, found that approximately 31 million people, nearly a quarter of Americans who have health insurance, are underinsured.

While there's not a universally agreed-upon definition of what it means to be underinsured, the Commonwealth Fund conservatively defines it using one or more of the following three measures: Someone insured for a full year whose out-of-pocket costs during that time (excluding premiums) amounted to 10 percent or more of their household income; a low-income household in which out-of-pocket costs were 5 percent or more of total income; or households in which the health plan's deductible equals 5 percent or more of household income.

Most people defined as underinsured are enrolled in an employer-sponsored plan. Since the majority of Americans are covered this way, the new Affordable Care Act marketplace plans haven't had a measurable effect so far on underinsurance trends, explains Sara Collins, vice president of health care coverage and access for the Commonwealth Fund, and coauthor of the recent study.

The study showed that while the percentage of underinsured adults hardly changed between 2010 and 2014, the rate is almost double what it was back in 2003.

Collins explains that 17 million Americans have gained coverage under the Affordable Care Act, which means that "fewer people are fully exposed to the full cost of care because of the increases in coverage, but the concern is that a trend toward higher cost sharing in private health plans might undermine those gains if more people are underinsured," Collins says.

Using the underinsurance measure that only considers a plan's deductible compared to household income, 7 million people were found to be underinsured as of 2014. That's more than triple what this same rate was in 2003.

"Every single year we're seeing an increase in people with high deductibles relative to their income," Collins adds.

Still, provisions of the ACA have forced insurance companies to include coverage for services — including preventive care — that previously weren't mandatory, says Washington Insurance Commissioner Mike Kreidler. Deductibles are also capped each year, Kreidler adds.

"This year they're limited to $6,850 for an individual. There were no limits before the [ACA] and deductibles reached up to $10,000 on some plans," he explains. "Also, some people with serious illnesses who reached their lifetime benefit limits had to pay out-of-pocket for further care."

A LEAKY SAFETY NET

For the Carrolls, Jenna's broken ankle required surgery, physical therapy and numerous doctor visits. The financial setback meant that the couple wasn't able to consider buying their first home until more than a year later than they'd hoped. Because her individual health plan through work — she's the volunteer and outreach coordinator for the Spokane Humane Society — had a deductible of $5,500, the couple was responsible for that full amount and then some.

"I knew it was going to be so expensive. I mean, this is the reason people have GoFundMe accounts when shit like this happens. These started rolling in, and it was really stressful," she says, pointing to her pile of bills.

Surgery (not including the anesthesia; that's several hundred dollars extra) to stabilize the bone fracture was billed at about $20,000, all but $4,100 of which was covered by Carroll's plan. Still, based on the Commonwealth Fund's measures, she is underinsured.

Then, halfway through post-surgery physical therapy, her insurance plan changed and that high deductible she'd previously met was reset to zero. Being forced to pay out of pocket again, she had no choice but to stop the rehabilitation.

The purpose of insurance is to create a safety net for a rainy day; when tragedy strikes. But not everyone — the Carrolls had a little bit saved up, but still went on a payment plan for some of the bigger bills — is well-equipped to handle the burden of several hundreds, or thousands, of dollars they may owe when the unexpected happens.

In a recent New York Times series examining the growing number of Americans saddled with medical-related debt, people across the U.S. shared their stories. Comments included anecdotes of failed mortgages, the need for second jobs, dipping into or draining retirement savings, deciding not to have children and even going bankrupt. Many also said they were afraid to go to the doctor anymore because of the costs such a visit might incur.

All of these issues are a major concern for health care providers, like physician Jeffery Liles, who practices internal medicine at Westview Family Medicine in north Spokane.

"I have a diabetic [patient] who has foregone the recommended medications because she couldn't afford it. Now we're trying to work through different prescriptions, going though the [drug] manufacturer to see if we can get coverage," Liles says. "Without a doubt, she has suffered. Her diabetes is really out of control."

While Liles says he now rarely encounters patients without insurance, the trend has definitely shifted to "people who have, essentially, regular employment and have these very high deductible plans."

From Kreidler's perspective, part of this high deductible problem is that most people are motivated to pick a plan with a lower monthly premium.

"Which is understandable, but they may not consider the impact of a high deductible, especially if they need more care than they anticipated," Kreidler says.

HEALTH CARE LITERACY

Rep. Jim McDermott (D-Wash.) is a congressional leader on health care who's been outspoken on the issue of underinsurance, calling it the "next big problem" in providing accessible, affordable American health care. On the campaign trail, presidential candidates also have presented potential solutions. Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders has openly proposed his "Medicare for all" government-run health plan that would eliminate deductibles and copays. Yet he's been widely criticized regarding his plans to fund it, mainly implementing heavy taxes on the wealthiest earners.

Hillary Clinton, meanwhile, proposes expansions to the ACA that would require providers to pay for up to three doctor visits a year. She also has suggested tax credits for those with high deductibles — amounting to 5 percent or more of household income — and would cap monthly out-of-pocket spending on prescription drugs.

Republican candidates, who collectively oppose the ACA's provisions, have been less vocal when it comes to solving the underinsurance problem. Other than vowing to "repeal Obamacare," they have not directly addressed the issue of underinsurance.

A major factor contributing to underinsurance — besides rising health care costs, stagnant wage growth contrasted with rising plan premiums and more Americans simply having access to insurance — is the complexity of choosing a health plan.

"We need to do a better job at helping people understand the trade-offs they make when selecting a plan, and the impacts their choices could have on their family budget over the year," says Kreidler.

He adds that his office offers some online resources to help make better insurance purchasing decisions, and mentions the compare-plan option and other features of the Washington Healthplanfinder exchange created to comply with the ACA.

"But more needs to be done to improve what we call 'health care literacy,'" Kreidler says. "Agents and brokers are also a valuable resource in helping understand how a policy works, and the trade-offs made when selecting a plan."

High deductible plans can clearly create burdens when disaster strikes, but from the perspective of Spokane physician Liles, they've also caused some providers and their patients to be more cost-conscious.

"When something is covered 100 percent, people never question the cost," he notes. "It's not all bad to have a little bit more skin in the game. When you look at a health plan with no deductible, utilization goes through the roof, but with a huge deductible you have decreased utilization."

Yet Liles is still frustrated when he considers his patients, like the woman with diabetes, who even with insurance can't afford basic care.

"The ideal would be, you have incentives that really promote health prevention, and people get it all — regular physicals and checkups, preventive medications and chronic diseases are covered — but then other things maybe go to a higher deductible," he suggests.

BACK IN ACTION

Since Carroll's ankle has fully healed, she's been able to lace up her derby skates again. Naturally, she doesn't want to relive the stress and pain of another injury, but the sport means a great deal to her.

"I knew what I was doing when I signed up for roller derby; that I could hurt myself," she says. "But I was depressed, and I needed a hobby and another identity that had nothing to do with my job."

So she and husband David agreed: she can have one more derby-related injury. If that happens, it's time to hang up her skates for good. Since that accident two years ago, the couple has been able to save enough that if something else like it were to happen, they wouldn't be caught in the same situation.

And though her injury was a major financial setback, the Carrolls finally were able to buy a home last fall. ♦

It's critical as a consumer to understand and compare how insurance plans work, what's covered and what's not, and that a low premium doesn't always equal low costs for you. Here are some helpful online resources to become a better informed health care consumer:

Know your plan and how it works — the Washington state Health Benefit Exchange offers a great graphic that breaks down the complicated world of health insurance. Find it at wahbexhange.org under the "current customers" menu option.

The Washington state Office of the Insurance Commissioner also offers a helpful list of things to consider when shopping for health insurance. Find it at insurance.wa.gov, under the "For Consumers" tab.

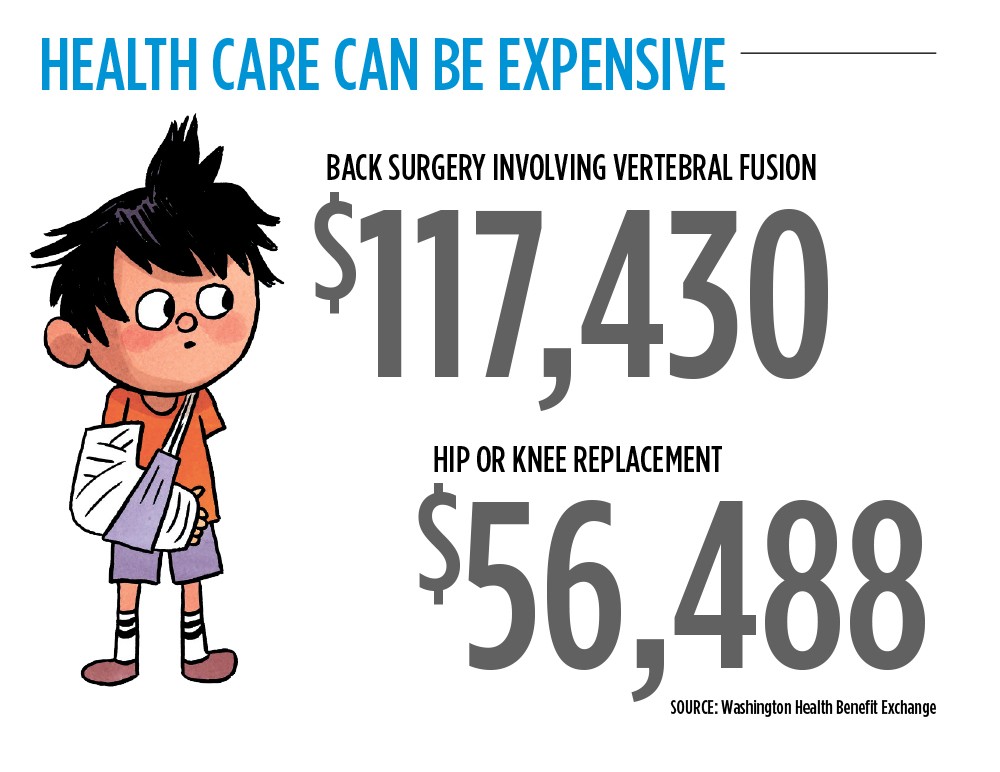

To research the estimated price of various procedures that may not be covered in full by your plan — until a deductible is met — Healthcare Bluebook (healthcarebluebook.com) lets users search by procedure (surgeries, labs, hospital care, etc.) to find out what the average "fair price" for a specific health care need is.