Diane Saffell has all the ingredients for a book. She has a knack for prose. She understands plot and character development. She has enough life experience to last, well, a lifetime.

With people encouraging her to finally publish her writing, the retiree attended monthly meetings of Spokane Authors and Self-Publishers.

“They make it sound like it’s so easy,” says Saffell, 67. “They don’t realize that it’s not an easy process.”

That may be changing, though, as the entire publishing and book industry is transformed by technology — in a way perhaps not seen since the development of the printing press.

What was once largely a field for people who were skilled (or lucky) enough to get book contracts and convince agents to sell their work is being turned upside down by digital publishing, e-books, tablet readers, Apple’s iPads and everything in between.

And don’t forget the proverbial 600-pound gorilla: Amazon.com.

“The big fear [among authors and booksellers],” says Spokane author and National Book Award finalist Jess Walter, “is that the only two publishers left in the end will be Amazon and Apple.”

E-books? Yes, Please

What has made the publishing process relatively more open — or smoothed out the hills people like Saffell must climb — is no secret. The ease with which information can be shared, obtained and downloaded online seems to grow with every passing day.

Authors can increasingly forego the sometimes-onerous book publishing process and publish directly in e-book format, thanks to a multitude of self-publishing options, including through Amazon.

As a concept, though, e-books aren’t new — they’ve been around in earnest for the better part of 20 years. Their deeper roots can be traced to 1971 and Project Gutenberg, a University of Illinois initiative to create a digital public library of 10,000 titles, according to a Guardian U.K. timeline. And then the online book project BiblioBytes created the first monetary exchange system for the then-fledgling Internet in 1992 to sell e-books, preceding the now-omnipresent Amazon by two years.

What is new is the ease with which consumers can find, purchase and read e-books. That has everything to do with how such books are primarily read: on tablets.

They go by different names and come in varying sizes, from numerous manufacturers. Apple, of course, has the iPad, about a year-and-a-half old. Barnes and Noble offers the Nook. Wireless company Samsung has the Galaxy Tab. Other companies, like Hewlett-Packard, with its TouchPad, have released and quickly retracted their tablets. This list of also-rans goes on and on.

And then there’s Amazon’s Kindle.

Launched in November 2007, the Kindle has become to e-books — and Amazon’s core business — what the Dodge Caravan was to soccer moms 15 years ago. It’s not the only game in town, and not even the flashiest or most user-friendly. (That distinction probably goes to the iPad.) But it has an attractive price, and it’s tied to what Amazon has a lot of: rights to sell digital editions of books.

The Kindle and its other tablet brethren have taken e-books from a quaint alternative for people who don’t have the need for physical books and placed them squarely in the mainstream. Amazon announced in May that it now sells more e-books (exclusively for the Kindle) than print books.

“It was a milestone, but I’m not particularly surprised,” says Alan D. Mutter, a former newspaper editor and cable/Internet company executive who now consults companies on digital technology. He is a frequent commentator on digital trends in news and publishing.

Mutter notes that, just as in any other market, book publishing is “driven by what delights the consumer.” That delight, he says, is tied to two very important and obvious factors: convenience and price.

E-books, especially on the iPad, are remarkably easy to obtain with a wireless cellular or Internet connection.

“It’s absolutely incredible how easy it is. It allows you to literally buy with one click,” Mutter says. Additionally, e-books are “substantially cheaper” than their printed counterparts.

In sum, a win-win for consumers.

Picking Up The Pieces

But the trend has its drawbacks. While readers are coming out ahead with e-books, authors and booksellers are potentially left to pick up the pieces.

Depending on your perspective, there may not be many pieces left of Borders, the now-defunct national chain that closed its doors this year. How long the writing was on the wall for that — and whether it was the result of e-book prominence or bad business operations — is debatable.

But there’s no doubt that Borders’ closing was in part a casualty of a changing publishing industry.

Such a milestone — if that’s what it can properly be called — is bittersweet for local, independent bookstores like Auntie’s. On one hand, you lament the loss of yet another store and what that means for the future of your own, the success of which is firmly in the non-digital camp.

But Auntie’s is still a business, and it needs to capitalize on opportunities — and they’re trying.

Store manager Melissa Opel says the Borders closure presents an obvious opportunity to attract new customers for whom shopping at another store was more convenient. Auntie’s is offering former Borders members a free discount card for its own store.

Opel has followed the rise of e-books, and print’s decline is worrisome on an aesthetic level.

“In [e-books] you lose a lot more. You lose the touch. There’s even smell that we associate with books,” she says. “You lose the ability to turn the page, to see your progress as you’re going through it.”

However, what Opel dislikes most is not the general concept of e-books. Auntie’s does have a structure in place to sell them directly to customers using Google E-books. Google partners with independent booksellers to share revenue on e-books downloaded by a particular store’s customers via its website.

Rather, she dislikes how Amazon has used its prominence to obtain rights to e-books and effectively force publishers and authors to accept lower prices for their books. Amazon sets the price of e-books artificially low and makes up for it by selling Kindles and Kindle-enabled devices that must be used to read the e-books it sells.

That practice doesn’t sit well with Opel.

“From an independent bookseller standpoint, it’s always sad to see a book treated as a commodity. Because it’s not just about selling a book. You’re selling imagination. You’re selling entertainment. And you’re selling knowledge. And all of those things are more important than getting $1.20 off,” she says.

The Authors’ Take

Bookstores and traditional print publishers certainly aren’t the only ones caught up in the brave new world of e-books.

Authors — you know, those people whose words you’re reading and buying — have just as much at stake. Local authors interviewed for this story — from self-published retirees to our biggest names — all seem to share the same sentiment toward e-books: cautious optimism.

Patrick F. McManus is intrigued by the opportunities presented by e-books, particularly the power of Amazon to bypass traditional publishers. At age 78, he admits he’s become cynical about the publishing industry, particularly the big publishing houses in New York with which he’s worked for many years.

His first book, A Fine and Pleasant Misery, came out in 1978. Since then, the Sandpoint-raised author, who lives in Spokane, has written nearly 20 books.

“The New York publishing business is probably going the same way as Borders,” he says.

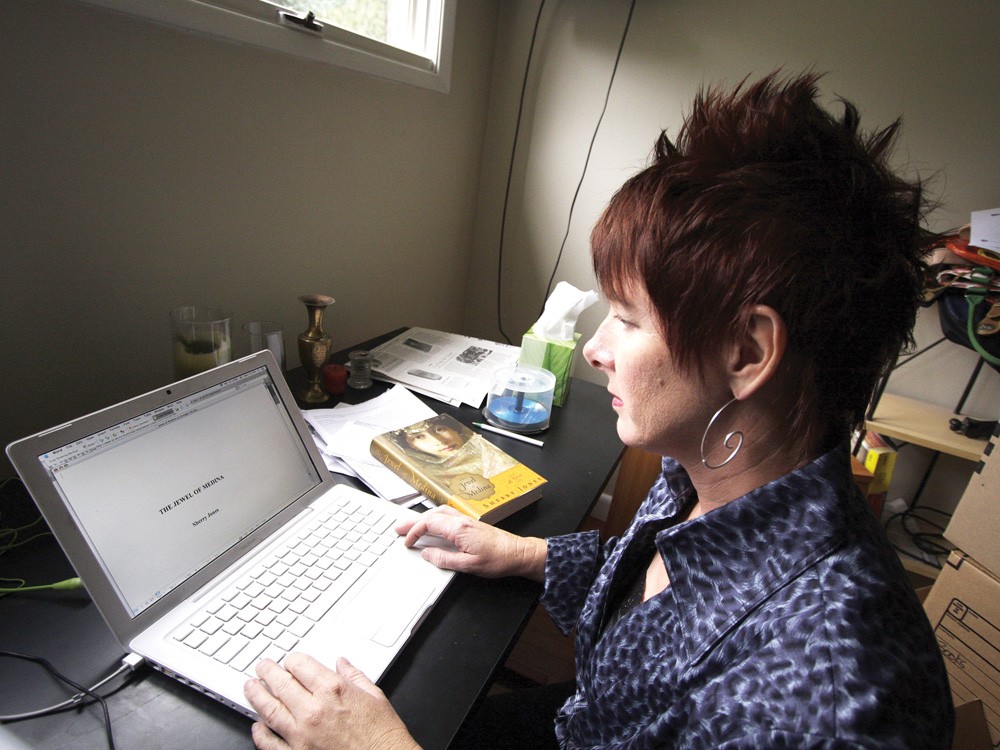

If ever there were an author who might like to buck the traditional publishing system and venture into self-publishing, it might be Sherry Jones. Her first book, The Jewel of Medina, was set for a 2008 release from Random House. For a first-time author, that’s quite an accomplishment.

But a professor reading a review copy warned the publisher that the book could incite Islamic extremists to retaliate, and Random House backed out. It was picked up by a smaller publisher, Beaufort Books, for U.S. distribution. Plans to publish in the United Kingdom were put on hold after the British publisher’s home was attacked with a Molotov cocktail.

Beaufort doesn’t offer the book and its sequel in paperback, only hardback, and as a result it’s not as widely available in bookstores.

Still, Jones says she wouldn’t branch out on her own or go to Amazon with a fully independent e-book. She calls publishing through Amazon “a double-edged sword.”

The process with e-books is easier, faster and offers more worldwide exposure. But, as is a common complaint from authors, “their books are priced too low,” she says.

Despite her reservations, she used Amazon to self-publish a short story called “Rapture,” meant to coincide with a Christian group’s warning that the end times were coming in May 2011. She set the price of the story — available only as a Kindle download — at $2.99, above the $0.99 that Amazon recommended. By her own admission, it was a flop, which she credits to her lack of time or will to market it entirely on her own.

Welcome to the self-publishing jungle: You’re free from large publishing processes and more control over your work — but you’re also a CEO and marketer as much as a writer.

Low e-book prices and Amazon’s market dominance have been a consistent criticism from Sherman Alexie, the nationally recognized author, poet and filmmaker. Alexie grew up in Wellpinit, Wash., attended high school in Reardan, Wash., and college at Gonzaga and now lives in Seattle. His book The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian won a 2007 National Book Award.

Alexie has been outspoken about his disdain for Amazon. He wrote on Twitter on Oct. 5: “At what point will Amazon’s publishing monopoly be large enough for them to begin raising e-book prices?”

He followed that on Oct. 12 with another tweet, writing: “Soon, Amazon will monopolize publishing, editing, book sales, and publicity. One place, one power. And you’re okay with that?”

Jess Walter reflects much of Alexie’s reticence, and resistance, toward the monopolization of books and e-books. But Walter, whose 2006 book The Zero was a National Book Award finalist, admits that there are definite “democratizing” elements to e-books being cheaply and freely available, such as for college students, who can download chemistry textbooks or the complete works of Shakespeare on a tablet reader without breaking the bank.

Walter and Alexie are nationally known authors with noted skepticism toward e-books and Amazon’s processes. If there are “camps” in this debate, Barry Eisler is in the opposite.

The successful author of Inside Out and Fault Line, among other thrillers, has made headlines in the publishing world by releasing his latest book, The Detachment, exclusively as a Kindle e-book. A paperback edition, also published by Amazon, came out Oct. 18.

Eisler talked about his choice to pass up a $500,000 book deal with St. Martin’s Press on NPR’s Morning Edition. He says that sales of the new e-book have “blown away” sales of his previous books.

Another benefit to e-books and tablet reading that’s more theoretical at this point is the ability to have multimedia experiences — incorporating text, video, music and interactive graphics into what was formerly just a strict reading experience.

User experiences like that offer great potential for non-literature authors like Coeur d’ Alene resident Susan Nipp, who, along with her business partner, Pam Beall, offered the Wee Sing book series with companion cassette tapes, CDs and DVDs. The pair began publishing the music education resources in 1977, and since then the Wee Sing series has sold over 60 million units.

Nipp agrees that the Wee Sing series and her children’s book Mudgy and Millie could work well outside the traditional printed book sphere, and she sees potential for a rich user experience with a tablet app. While she says she keeps a foot in “the old world,” she knows that authors need to recognize the present and future realities.

“We need to adapt and figure out how to make these changes,” she says.

Walter, however, isn’t so keen on the idea of readers being potentially distracted by other capabilities of the tablet on which they’re reading his books.

“That communion between writer and reader, I don’t want to be broken by them being able to check their email or taking a quick Internet porn break,” Walter says. “I want them to finish the book [and] keep their hands to themselves.”

For Whom The Bell Tolls

In a back room of the North Division Old Country Buffet, about 40 authors, writers and poets have gathered. Between bites of lasagna and iceberg-lettuce salad, they discuss their successes and strategies.

It’s a mostly-older crowd, retirees in many cases, coming for a monthly meeting of Spokane Authors and Self-Publishers. Some members are published, and they display their books proudly on a table up front.

Members and guests are smaller-scale writers, some published, some not, and the books displayed aren’t on any national bestseller list. But the successes they announce — and the drive to share their writing — are no less laudable than those of any other author.

Guest speaker Vic Bobb speaks at a meeting of Spokane Authors and Self-Publishers at an Old Country Buffet

Club Vice President Bob Weldin runs the meeting, holding up his manuscript of The Dry Diggin’s Club, based on his career as an exploration geologist. This is the “bell ringing” segment, when club members talk about successes they’ve had and literally ring a brass bell.

Weldin recently finished the manuscript, and hopes to get it published — whether through traditional means, a self-published option or, who knows, an e-book.

“Doesn’t matter. I’m going to publish it anyway,” Weldin says. He rings the bell. Ding.

Another woman won a competitive poetry contest. Ding.

Jim Parry’s title Book All the Teachers is now available on Kindle and Nook. Ding.

Diana Wickes didn’t have a bell to ring this time, but she might in the future. The 81-year-old wants to publish a historical biography about her mother’s time growing up as a German in Jamaica. She came to the U.S. infused with historical points of reference, like Charles Lindbergh’s cross-Atlantic flight.

What form that publishing takes, ultimately, isn’t important, she says.

“I’d be happy to have something published in digital form,” she says. “I’m not interested in profit.”

Comments? Send them [email protected].