Two weeks ago, Sheriff Ozzie Knezovich announced a round of layoffs at both the downtown jail and Geiger Corrections Center in Airway Heights. The hit was big: 57 jail employees would lose their jobs. A week later, after more budget-crunching, the sheriff said he needed to lay off an additional 10 staffers in detention services to fill the budget hole.

The reason: Inmate population was way down, and no one could for sure say why. Yes, the prosecutor’s office is seeing fewer cases and had attempted to institute a program that resolved cases much more quickly. Violent crime is down across the nation. A recent ruling by the U.S. Supreme Court has made it harder for cops to search cars without a warrant, leading to fewer arrests.

The sheriff built his budget with the assumption there would be an average of 930 inmates a day between the two facilities. Reality brought in only 768, nearly 300 fewer than this time last year. Missing the mark tore an $8 million hole in the budget.

For some, this reality — a low jail population sustained over the last five months — has called into question a project that Knezovich and others have been pursuing, the Detention Services Project. It’s the $160 million-plus jail expansion, first conceived when daily inmate populations pushed well beyond 1,000.

But now, with the jail population falling and numerous layoffs, questions have arisen about why Geiger suffered the deepest staff cuts and whether the jail even needs to be expanded at all.

“It’s time to re-think this,” says County Commissioner Bonnie Mager.

“If we can be this successful without even implementing the things we’ve told will reduce recidivism, then let’s invest in those first and see how those work. … That way, we can tell people we’ve done everything we can.”

Jerry Brady, the county’s former jail commander, wants to make one thing clear: He’s a conservative. Bad guys belong behind bars, end of story. But for him, the story’s gotten complicated in the year and half since he retired.“If there’s need, I’m all for it,” Brady says. “I’d be out there beating the drum and saying, ‘We have to do this.’ But why now? Now is not the time.”

When he was commander, the downtown jail had a population of about 620 inmates and Geiger had 500, a grand total of more than 1,100 incarcerated people. At that time, Brady was supportive of jail expansion. The two facilities were under too much pressure, and there was no other reasonable way to relieve it other than to create more beds.

But now, Brady points out, there are 768 inmates in an institution that can theoretically hold more than a thousand. And yet the sheriff is still pushing for expansion.

“It’s smoke and mirrors,” Brady says. “What you’re building the new facility for is overflow. Now there is no overflow. And I don’t think there will be in the foreseeable future.”

“It’s hard to understand how this could have possibly snuck up on everybody,” says Gordon Smith, the union representative for most of the jail staff at Geiger. “I mean a month ago, I was in a meeting with [the jail’s supervisors] and they were saying everything was good. It’s baffling.”

Smith, like many at Geiger, can’t explain why the layoffs took out almost half of Geiger’s employees, while skimming only 10 percent from the jail. But he has his ideas.

“The inmate population has been spiraling down for a year now,” he says. “Given the strong interest in the sheriff wanting to build a new jail, maybe they didn’t want to believe it.”

Brady agrees. “It’s a star on his resume,” he says of Knezovich building a new facility. “He’s a very determined person. Once he gets it in his mind, he doesn’t change it.”

Aside from the jail population, the prime reason for a new, expanded facility is the impending closure of Geiger, prompted after the Airport Board suggested that a detention facility was no longer welcome on its land.

But even this has been called into question. According to state law, in RCW 14.08, airports owned by municipalities are under “the exclusive jurisdiction and control of the … municipalities controlling and operating it.” The Spokane International Airport is jointly owned, controlled and operated by the county and the city of Spokane.

“One big myth is the airport authority is making them leave,” says Breann Beggs, an attorney with the Center for Justice. “They can’t make them leave. There are some people who would like Geiger to not be there, but they can’t make them leave, for sure. … It’s unclear whether [the Airport Board] even had a vote on this.”

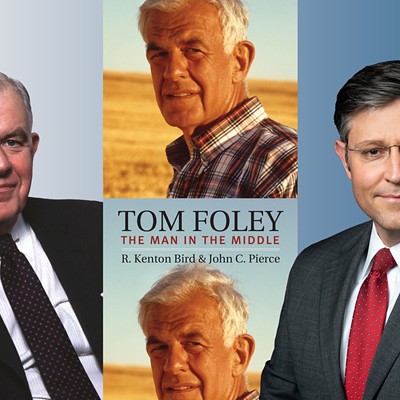

Sheriff Ozzie Knezovich at this year's Spokane County Republican Party convention. [Photo: Young Kwak]

Knezovich is adamant on one fact: The jail is still overpopulated.

“I have a 750-bed problem,” he says. He’s sorry that the budget miscalculation cost jobs — “It came at a very high human cost,” he says. But, he says, his administration is diligently doing something no one did before.

“We’ve been slowly and methodically rebuilding the criminal justice system,” he says. “We’ve done exactly what the experts said to do. … What no one can explain is this rapid decrease [in inmates]. What we’re trying to figure out is if this is sustainable or if it’s just a bump.”

But perhaps the sheriff’s reforms have led to a permanent drop in jail population. What then?

“If we can sustain the jail population for the next six months, then we would know that this is sustainable.… If that’s the case, we’ll look at the entire jail project and see if we need to reduce its size,” Knezovich says. But scrapping the entire project is very unlikely. An expanded jail would not be needed “if we can get the jail population down to 500, and that would have to be sustainable for the next 25 years.” In other words, impossible.

According to an official 2008 study that was prepared for the county about the criminal justice system and the jail expansion, one sure way to manage the jail population was through Geiger.

In the first six months of 2007, almost half the inmates (about 240) there were doing something other than being simply confined.

Some lived off-premises and were electronically monitored. Others took part in a work release program, where they went to work during the day but slept at the jail. More were in work crews, where they performed tasks for the community, such as collecting trash, shoveling snow and tending wildlife refuges.

In a bid to streamline county government, the management of Geiger shifted from the county commissioners to the sheriff’s office on Jan. 1, 2008. A new sheriff, so to speak, was in town at Geiger. His name was Ozzie Knezovich and he had a different way to run things.

The sheriff’s budget provides for a lot of things (a helicopter, explosives disposal and patrolling our streets, to name a few), but virtually nothing for these programs at Geiger — which are proven to reduce pressure on the jail, provide affordable alternatives to incarceration and address high rates of recidivism (inmates re-offending after being released).

In other words, they’re all ways to keep the inmate population down. And before Geiger was shifted to Knezovich’s control, the entire facility ran as an enterprise fund, meaning it had to be self-sustaining and cost-neutral.

“We recovered our cost with those programs,” says Chris Wiese, the jail’s finance director, of Geiger’s community corrections programs. “They had to be cut because last year, we had to cut $3.1 million [from our budget]. By law, we had to look at those services that weren’t mandated.… If you don’t have the money, it doesn’t matter how good the programs were. Nobody ever challenged the validity of those programs. Nobody wanted to cut them.”

But many are finding it difficult to understand why programs that cost nothing (in the annual equation) nevertheless had to be cut. What is saved by cutting something that is virtually free?

Knezovich says calling these programs self-sustaining is “half true. The county had to pay for it and then we would have to charge the customer.” In this case, the customer was the inmate.

He points out that in 2004, before the sheriff’s office took Geiger over, the facility’s supervisors requested an additional $1 million because the facility wasn’t charging the inmates enough for the programs they were involved in. (Inmates being electronically monitored paid for their own ankle bracelets, and work release participants paid a fee to sleep at the jail.)

For him, it’s about balancing the equation correctly.

“They’re self-sustaining until [we stop] getting inmates,” Knezovich says, comparing the jail’s budget to a food chain that can get thrown out of whack if one part of the system is changed.

Others see another reason why the community corrections programs were cut.

“Politics could’ve been in play, but I’m speculating,” says Smith, the union representative. When the county commissioners called for an across-the-board cut to every county department, Knezovich bristled, Smith says. He took aim at programs that the commissioners considered important.

“Cut something that’s really valuable and then they won’t cut the budget,” Smith says. “The bluff was called.”

Knezovich says community corrections are important to him and that he had no choice in where to cut his budget. He had to pay for deputies patrolling the streets and confinement. “We didn’t kill all our programs. As a matter of fact, we’ve been slowly bringing our programs back.” The jail still employs some work crew.

Saying that the sheriff doesn’t care about rehab programs just isn’t true, says Spokane Municipal Court Judge Mary Logan.

“I don’t think it’s a fair criticism at all,” she says. “He was instituting parenting classes and fathering classes because he realized how important it was … to stop the cycle in the family.”

Others aren’t so sure. “You tell me you want more money, but you’re laying off upwards of 70 people [and] want a new facility,” asks Brady, the former jail commander, in disbelief.

“That just doesn’t make sense to me.”