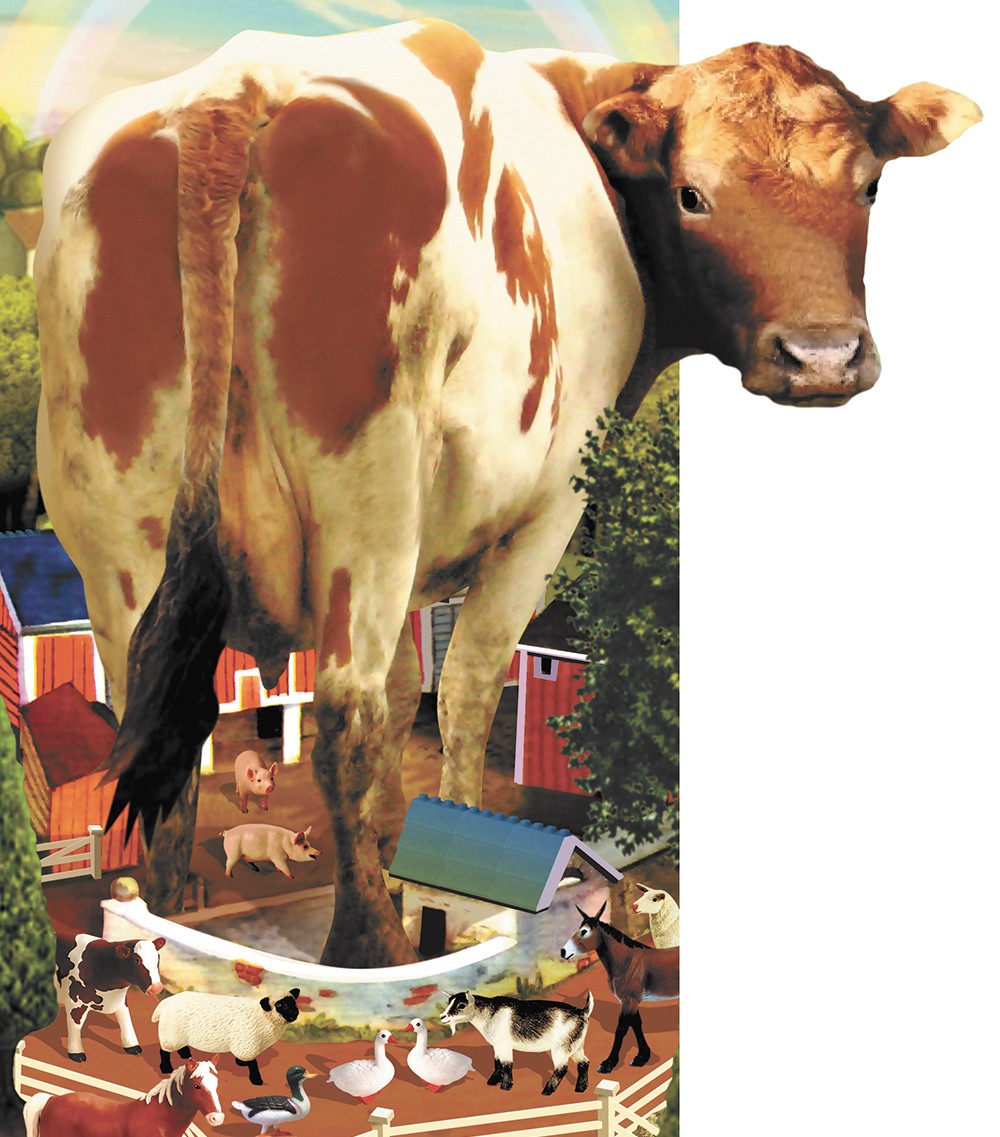

So much waste. Millions and millions of pounds of the stuff each year — a disgusting by-product no one really wants, most of it free for the taking and chock-full of unused raw materials. Erik Coats, an associate professor of civil engineering at the University of Idaho, took stock of the more than 8,000 dairy farms statewide, all of them brimming with manure.

He could smell great potential, among other odors.

"Historically, we've viewed waste streams as bad," he says. "[But] it's a raw resource that we can process into something valuable."

Coats now leads the nation's only research team successfully processing cow manure into a type of cheap, versatile and, most important, biodegradable plastic — polyhydroxyalkanoate or PHA — with a growing variety of uses.

Much of his research requires working on-site at dairy farms using a mobile processing facility built within a 24-foot trailer. It means slopping through gallons of wet manure and embracing the dirty work of discovery. He notes his colleagues don't always appreciate the aroma of his lab.

"Not all researchers are willing to work in that environment," he says. "Part of it is just the yuck factor. ... Some people might not think it's sexy, [but] there's a real need out there."

As natural and agricultural resources dwindle, it becomes increasingly important to know how to recover valuable material from waste, he says. In pursuit of a more sustainable world, Coats says he expects more and more future research will focus on giving industrial by-products, things like cow manure, a second life through science.

"It's pretty cool stuff," he says. "I get excited about it."

The final product often resembles a clear sheet of film, like plastic wrap, that can serve many different functions. It's quite similar to common petroleum-based plastics like polypropylene. Coats says it works well for single-use packaging. Being biodegradable, it also works outdoors for plant potters or erosion-control matting.

But it all begins with the back end of a cow.

Coats and his team of UI graduate students take raw, wet manure and process it through a fermentation tank. During fermentation, carbohydrates in the manure break down into organic acids like vinegar. Coats says it's not so different from how beer fermentation produces alcohol.

"At a certain level, it's the same process," he says. "[Instead of yeast], it's just a different microorganism."

Coats then feeds those organic acids to a special bacteria that stores its leftovers as PHA. His team can then dry and harvest out granules of the plastic and purify them into usable material.

The Idaho State Department of Agriculture reports the state has more than 540,000 dairy cows, each producing literally tons of manure every year. Coats says approximately 12 gallons (about 100 pounds) of raw manure can process down to five pounds of PHA plastic.

While the manure-based plastic ends up very similar to other plastics, Coats acknowledges most people might hesitate to use it for some applications, such as food storage. He says the plastic would be plenty sanitary, but doesn't plan to waste time trying to convince people when there are so many other good ways to use the product.

"It's just plastic," he says, regarding food-storage applications. "Would it be appropriate? Sure. Is it a path we want to go down? No."

Coats says his graduate students, the true workhorses of the effort, have helped him study the process at all levels in hopes of improving the predictability of the reactions and yields. He also wants to secure funding this year for additional equipment to help separate wet and dry materials from the manure, improving the efficiency of the process.

After spending years working out of a trailer, refining and studying the process on a small scale, Coats plans to move his research toward commercial viability on an industrial scale. He wants PHA to "leave the lab" and find its place within the country's manufacturing and production practices. That's where his dream of turning waste into resource can really shape the world.

"We need to be ... maximizing recovery," he says. "We need to take that next big leap."

In 100 years, the thoughtful recovery of material from waste streams may be routine, Coats says. He hopes this work will be his contribution to that more sustainable future.

"We can do better," he says. "Leave it better."

So while some scientists chase after genomes or black holes or other glamorous projects, Coats will keep working in the muck. Somebody has to do it. ♦