Spokane Police Officer Dan Lesser says the shotgun was pointed right at him. That's why he fired his semi-automatic rifle at James Rogers in 2011. Lesser fired two bursts in rapid succession — boom boom boom! boom boom boom! — with six shots total. Four rounds struck Rogers in the face, neck, hand and shoulder. He died at the scene.

Lesser was cleared of criminal charges as well as internal policy violations.

However, after reviewing the case file and autopsy, Rogers' family is not convinced by the police narrative. In 2012, they requested that law enforcement conduct additional tests. They sought to corroborate officers' claims that Rogers' shotgun was pointed at Lesser.

Police declined to conduct further testing of the evidence, specifically a blood spatter analysis, saying such an investigation would not lead to any reliable conclusions. That left Rogers' family with a decision: Accept the police account of the incident or pay for more answers out of their own pocket.

"I just had to know what happened," Rogers' father, Alonzo, says now. "If the evidence would have shown that he was pointing the gun at these officers, I would have understood that. I would have accepted that."

Alonzo Rogers, 70, came out of retirement in order to make extra money to pay for the additional investigation. So far, he has spent $15,500, he says, in part to hire forensic expert Chesterene Cwiklik.

Cwiklik, a former Washington State Patrol Crime Lab forensic scientist, ultimately concluded that the shotgun could not have been pointed at Lesser, and that Rogers was not looking at the officer when he was shot.

For James Sweetser, the attorney representing Rogers' family in a lawsuit that names Lesser and the city of Spokane, Cwiklik's conclusion is only the latest wrinkle in an investigation he says was doomed before it started.

"I've worked with the police, and I have reviewed investigation after investigation, and I've asked them to do additional investigations," says Sweetser, who served as the Spokane County prosecutor from 1995 to 1998. "It's very difficult in these situations, because an investigation that shows that something is wrong can subject the city to civil liability. But that can't be the focus when it comes to use of police power."

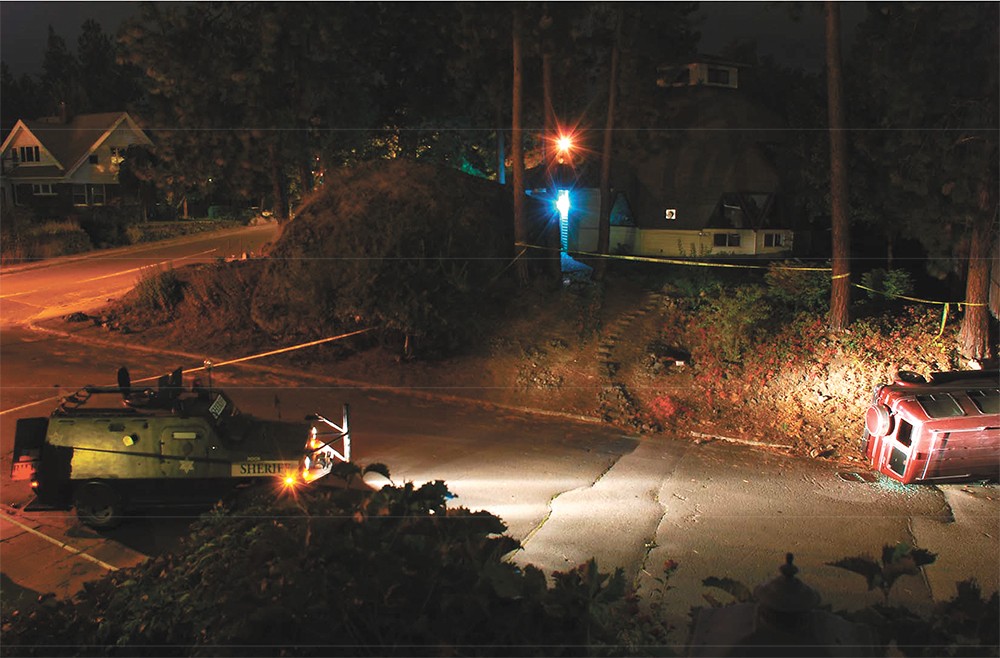

James Rogers was holed up in an overturned van with police rifles fixed on him. The 45-year-old recovering alcoholic suffered from depression and maybe bipolar disorder, his family says. He'd been through rehab and counseling, and in September 2011, he had been doing well until he wasn't again.

After a recent DUI and missed court date, Rogers was facing the possibility of losing his job at an assisted living facility for disabled people. There was a warrant out for his arrest and he was looking at possible jail time. He started drinking and decided it wasn't worth it. He wanted to die, a suicide note would say.

Rogers took his father's shotgun and drove to the parking lot where he worked at SL Start on the lower South Hill. He wanted to say goodbye to co-workers and friends, according to witness statements. In the parking lot, he fired the shotgun into the air once and drove off.

Police followed, and Rogers soon rolled the red van onto its passenger side. His body was wedged against the passenger door and the roof of the van. Local law enforcement surrounded the overturned vehicle and began negotiating with Rogers through a loudspeaker. He responded only by moving his feet and legs when asked if he needed medical attention. His sister, Angela Crigger, talked with police on the phone. She told them that this wasn't the first time he had attempted to end his life.

The standoff lasted nearly two hours. It ended when Lesser, then a 16-year veteran of the Spokane Police Department and a member of the SWAT team, fired six shots into the van's rear window.

Lesser has been involved in three other shootings since 2003 — more than any other SPD officer, according to public records. He's been cleared in each case. He also received a lifesaving award in 2008. In his deposition, Lesser said he was not trained to handle people with mental illnesses when he responded to Rogers, Crigger says.

Seconds before Lesser fired those fatal shots, SPD negotiators were trying to get Rogers to surrender.

"James, this is not a solution, bud," police can be heard saying that night. "Your whole family is worried. They need you. We understand you have seven kids, they will need their dad in the future. They will need to talk to you... "

Lesser fired. Rogers was pronounced dead at the scene, and his family began looking for answers. As information began trickling out, they became convinced that his death could have been avoided.

Here's why:

• Officer Kellee Gately, one of the officers talking to Rogers through a loudspeaker and watching him through binoculars, spoke with investigators the day after the shooting. In that interview, she said that Rogers was pointing the gun in the opposite direction of Lesser, toward the van's windshield, when the officer fired. In a sworn statement in January 2016, Gately reversed her account: "I saw Rogers quite deliberately move the gun in the direction of Officer Lesser," she states in court documents.

• Immediately after the shooting, Lesser and several officers on scene were taken to the Public Safety Building and waited together in the chief's conference room for a detective to arrive. Sweetser says that fact alone raises serious concerns.

"You don't let all the witnesses get together and talk about it if you really want to get to the truth," he says. "Separate, interrogate, don't let them get their stories together. That's a basic investigative technique if you want to get independent recollection that isn't contaminated by what someone else says happened."

Jeffry Finer, an attorney with the Center for Justice who has handled police misconduct cases, agrees with Sweetser's assertion.

"It's my impression that law enforcement in this town have been allowed to meet or interact in order to sharpen their recollections," Finer says of his experience generally. "That is not a procedure that would be favored or allowed for citizens."

• A video taken by a citizen contradicts how multiple officers describe Officer John Gately's voice as he negotiated with Rogers an instant before shots are fired. Multiple officers describe John Gately's voice as "excited," "stressed," "urgent" or "elevated." The video does not support those descriptions, says Sweetser, who argues that officers' mischaracterization is purposeful to justify Lesser firing.

• The autopsy report indicates that all of the bullets that struck Rogers traveled from the left side of his body to the right. Sweetser argues that those findings indicate that Rogers was not facing Lesser when he was shot, but was looking ahead, toward the van's floor.

• A blood spatter analysis by Cwiklik, the former WSP Crime Lab forensic scientist, found spatter on the right side of the shotgun, indicating that Rogers was not "shouldering" the shotgun as officers described, she says in her report.

Spokane police spokeswoman Michele Anderson declined to comment for this article, citing the pending lawsuit.

However, Stewart Estes, the attorney representing the city, hired his own expert who rebuts Cwiklik's conclusions.

Still, Sweetser says the detective's and prosecutor's refusal to conduct a blood spatter analysis is telling.

"Why aren't these questions being asked? Why aren't they digging in that way?" he says of the blood spatter analysis. "Is this procedure of investigation involving police officers the same rigorous investigation when it comes to a homicide involving a citizen? It should be the same, because a human life is a human life."

The James Rogers that Crigger, his sister, remembers is the guy who sat surrounded by his young kids and nephews, wearing 3-D glasses and watching Hannah Montana.

"It was so cute, he was really into it with them," she says. "He was so good with kids."

She remembers the Rogers who, when he came home on payday, would open his wallet and give a $20 to each kid in the house. He took joy from his job caring for disabled people and would regularly spend his own money to buy them pizza and birthday cake, she says. Once, he took two of his patients to Silverwood to fulfill their dream of riding a roller coaster.

Yet he still struggled with alcoholism. Rogers was an Army MP, his dad says, and started drinking after he left the service. He'd spiral into depression, but always managed to pull himself back up. He'd done stints in rehab and counseling.

After they pulled Rogers from the van, police found a citation for a DUI and a suicide note. It reads in part: "45 years is enough for me. I love you all and this is hard. There is nothing anyone could do to stop me. There will be no blame except for me and alcohol."

His blood alcohol content was .26 when he died, according to a toxicology report.

The city of Spokane requested summary judgment in the lawsuit, which would have allowed a judge, rather than a jury, to decide the outcome of the case. In his motion, Estes, the attorney representing the city, relies on a police expert in use-of-force decision-making to argue that Lesser was justified in shooting Rogers, regardless of whether Rogers was pointing the shotgun.

"It is irrelevant that Rogers (supposedly) did not point the weapon at Officer Lesser," court documents read. "Deadly force was still authorized given the extreme circumstances."

Judge Stanley Bastian denied the city's motion. He notes that officers are not justified to use deadly force on an armed suspect who has not committed a significant crime or threatened anyone. The fact that Rogers was suicidal does not justify deadly force either, Bastian ruled.

If this case goes to trial, jurors ultimately will be asked whether they believe the statements of officers on the scene that night, or the physical evidence as interpreted by an expert hired by Rogers' family.

"Our position is that physical evidence doesn't lie," Sweetser says. "It just sits there waiting to be analyzed." ♦