I learned to read early and discovered rap before I probably should have.

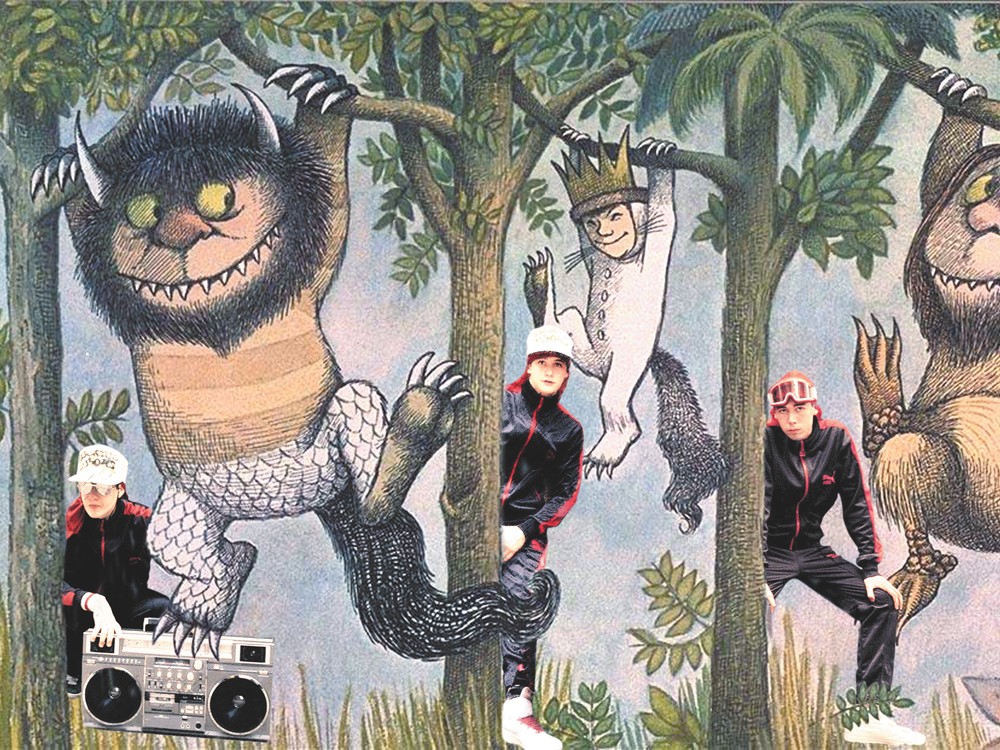

The reading was according to plan. My parents read to me incessantly — night and day, to hear my mom tell it — all to make little Lukey a boy genius. Where the Wild Things Are was a favorite of both parent and child, though probably for different reasons.

The rap came despite my parents’ best efforts. They (we) were part of a church that taught that everything not explicitly Christian was probably evil (and even then, Christian metalheads Stryper were regarded as a Trojan horse for Satanists). My mom had tossed her Black Sabbath and Fleetwood Mac records before I was born.

Her parents, though, were more lenient, and their youngest son, my uncle Mike, was only a decade older than me. I spent a lot of my childhood at my grandparents’ house, and under Mike’s tutelage, I was listening to the Beastie Boys’ Licensed to Ill by the time I was 6 (which led to NWA by the time I was 7 and 2 Live Crew by the time I was 8, but those are other stories entirely).

It was an odd mix of prohibition and permissiveness, and it left me at once devouring culture wherever I could get it (MTV, Hastings, my friends’ parents’ VHS porn stashes) while feeling incredibly guilty about all of it.

The guilt caused me to lash out more times than I care to remember, but not as much as I might have. Books like Wild Things and tapes like Licensed to Ill allowed me to have a secret world of rebellion without actually rebelling that much.

They were both bratty and explosively imaginative, and led to a very strange period (I’m going to place it approximately between age 6 and 7) in which I spent half my time in a fort made out of blankets and couch cushions trying to invoke the wild rumpus and the other half sitting in my uncle’s small bedroom fighting for my right to party. (Mike was a good tutor, explaining what brass monkey was, who Abe Vigoda was.)

When the Beastie Boys’ Adam Yauch died on May 4, I felt as though I had lost a mentor.

When Maurice Sendak, author of Where The Wild Things Are, died four days later, I had very similar feelings.

Mentors of what, though, has been harder to figure out.

I've spent the last couple weeks listening to a lot of Beastie Boys. I went out and bought a copy of Wild Things. Here’s what I think I’ve figured out: They acted as both a balm for me — against a world I thought was hostile to my cravings — and a prod — toward an adult life where the possibilities of imagination are the main reason I get up in the morning.

I’ve realized that, like basically everything I worshipped as a kid (see also: Star Wars, The Footloose soundtrack, Big League Chew), neither Licensed to Ill nor Where the Wild Things Are can match in reality the colossal monuments I’ve built to them in my mind. They aren’t as breathtaking or transgressive as I remember.

But I’m also realizing that they’re more complete than I had thought. Take the arc of the Beastie Boys’ career, the way it went from frat rap to the pioneering sound of Paul’s Boutique and the social consciousness that evolved alongside the music, then couple it with the fact that Yauch and company never once rejected the band they had once been. They just shrugged, apologized where necessary, and made of it what it was — a halting, sometimes painful, process of growing up.

There is a creative comfort in their body of work that I strive for and haven’t fully found. It’s the comfort of knowing, I think, that people will stick with you even if you’re a jerk, as long as you stay honest about it.

That’s where Wild Things dovetails. I remember Kid Me feeling like the end of the book — Max heading back home — was kind of a cop-out, or at least a surrender to the prosaic. The way his mom leaves dinner out for him, though, illustrates something I think seeped in even if I wasn’t consciously aware of it.

The people that care about you and that nurture that spark of imagination — even if they don’t always take the trip right away (Max’s mom, the Beasties’ fans) — will hang around, and stick it out with you, no matter what a bratty asshole you decide to be.

Even if that takes “night and day, in and out of weeks, for almost over a year,” these people will continue to love you.

For a kid who wanted freedom and whose imagination was his best outlet, and who had the capacity to be a massive asshole to his parents, these were important lessons.

So thanks for that, Adam. Maurice. Mom. Dad.